TW: historical suicide.

First, a big thank you to all subscribers as we passed a big milestone for this newsletter: over 5,000 subscribers! We are now at 5,061 Shangriloggers, with 340 of them getting the extra paid edition every week. If you enjoy this newsletter, consider joining those supporters. It’s what keeps this project going.

In a forgotten mining town, the mines aren’t the only thing lost to time. Just up the hill, a little northeast from my cabin, there is a cemetery. It is not fenced off, and there is no marked path to it. It is hardly maintained at all, save for the one plot added in 2021. You can still be buried there, assuming you’re from here, but the remaining headstones tell a story of a time long gone – one of hardship and loss. Of trying to make it through only to never make it out.

On the day we moved in, there was a funeral procession at the cemetery. Cars with license plates from all the West lined the streets, paying their respects to a friend lost too soon and laying him to rest as close to home as they could. It had been decades since someone had been buried there, but the soil is rich with patience, always making room for her children to return.

In avalanche country, bodies move. They’re pushed under the ground by moving soil while their tombstones are pushed by snow and rain and time down into the riverbeds and creeks. Headstones are cracked and faded by the elements back into the stone they came from. The remaining few monuments to the dead are scattered through the spindly aspens, fertilized by the bodies beneath them. Their kin all long since moved on, to elsewhere or to join them, and no one left to repair the graves or revere the dead.

But I do say hi. For whatever connective tissue there might be between us and the underworld, I try to follow the thread to the past, to acknowledge where I stand on the mountain with joy is where they once stood with hope. I try to let them know it’s still beautiful. I try to let them know there’s something of them still here in this valley of wind and snow, that they’ve persevered through time. I try to say hi when I can.

This past week, I went again to visit them. They are neighbors, after all. This time, I wanted to know more about them. This time, I did research. There are a few happy stories of long lives and jovial fellows, but only a few. The rest are a painting of a life riddled with disease, poverty, desperation, and blind hope, if there is any of the painting left at all.

First, there’s Pearl, short for Permelia. Daughter of not just the Joseph Edward Marchand mentioned on her tombstone, but of Marie Arthemise Beaudry Marchand who ran a hotel in the town over — lodging $6 for the week. Pearl married Gideon Baril on July 5, 1893 at 18 years old. They left for the Alaska gold rush in 1895, but Pearl returned. Eight years after her return in 1903, she committed suicide by drinking carbolic acid. Pearl’s tombstone sits alone.

I spent a long time in the archives, searching for names from the graveyard, finding family histories and businesses long since closed. But it wasn’t until I expanded my search to the names of old mining locations alongside “burial” and “cemetery” and “funeral” that the reach of how many gravestones were lost struck me, how many may not have had headstones at all.

Pearl’s death is not unique, then or now. Outside of Alaska, nowhere in the United States has a higher suicide rate than the Rocky Mountains. It’s true now, and it was true then. For all its beauty, it is an isolating and difficult place to live.

Alongside Pearl, somewhere in that plat of land, lies Maud Davis. She died in 1900 from morphine poisoning, along with Loren Evans, the 17-year-old son of a flume walker who shot himself in the head in 1916. Their gravestones are gone, but their stories live on in the archives — a reflection of their reality filled with grief and sorrow. Then there’s Andy Emerson.

The newspaper article reads: “he put an end to his earthly career last night by placing a stick of dynamite under his head and calmly awaiting until the fire from a short fuse ignited the cap.” He was 40. A fellow miner, Frank Fox, told Andy he was heading out to get provisions. Andy said he would wash some shirts in the meantime.

When the coroner was presented the body, he said, “I found the body lying in an easy position on the floor of an old stope, and it is very evident from all indications that after Fox left the bunk house the man went to the magazine, secured powder, fuse and caps and deliberately affixed the fuse and cap to the explosive, lit it, laid down, placed the powder under his head and calmly awaited the result.”

He had $485 in his pockets — nearly $16,000 in today’s market.

One word I could have searched all by itself in the archives was pneumonia.

Eric Erickson, pneumonia. 1899. No headstone.

John Brown, pneumonia, 1899. No headstone.

Jacob Hilber, pneumonia, 1906. No headstone.

Victor Colmer, pneumonia, 1903. No headstone.

Stephen Greigg, pneumonia, 1903. No headstone. He was twenty years old. Fell 100 feet in a mine only to survive and die of pneumonia days later.

Their bodies all interned across the street from our leach fields and wood piles. I say hi because they were robbed of too many.

And then, there are the children. Peter Giackelini née Jacolini, six months old, 1907. His sister Ester, born two years later, and lost in 1915 to diphtheria. Just five years old. The boy George Tatum, scarlet fever and uraemic poisoning, 1908, headstone never there or long lost. The newborn baby of Raymond and Mrs. Buss, weighing 16 ounces when born, kept alive sixty hours in an improvised incubator made of a shoe box with bottles of hot water for warmth.

There’s a gravestone simply to the members of the Jicarilla Tribe No. 63. As far as I can find, there’s no article about what happened or why the mass grave. The only mention of them in the region is one of the tribe throwing a ball where all the locals attended and everyone had a grand time. It’s a beautifully carved tombstone in a prime plot.

The winds are howling this morning as wet snow lays the remaining grasses to the ground. The sun is fighting to emerge through the dense clouds, a glowing calling in the massive gray sky. A reminder of the good lives lived here: Jimmie Noyes, a colorful character full of stories, lived to 1967. Nellie Tatum, lived here for sixty years before dying in 1956. “This is God’s town” inscribed on her tombstone. Bob Pryor, “a splendid fellow, but one of the old school of miners who usually has nothing to say regarding his family nor anything to say regarding himself.” Geo Smith, died at 78, after living in this town for over 30 years. Every single resident came to his funeral.

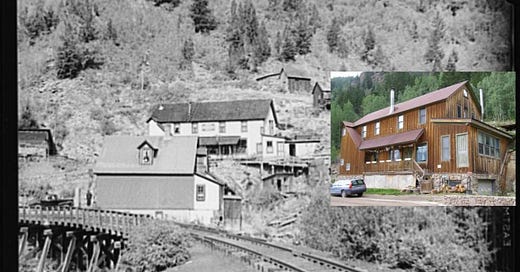

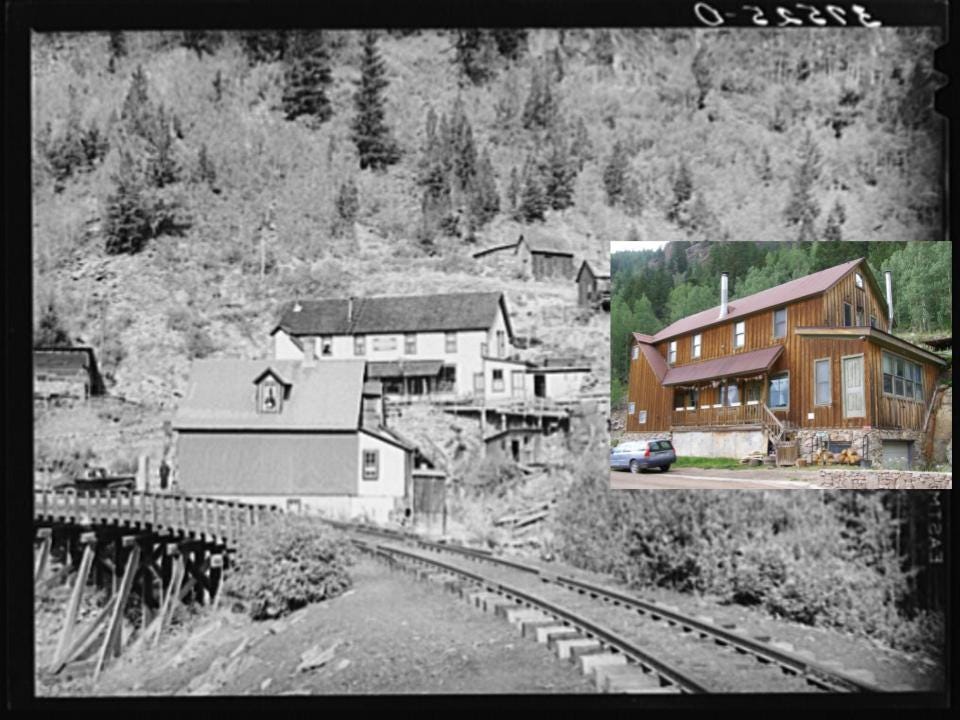

For all the loss, people came here for the reasons they still do: they’re looking to change their lives. Once for gold and silver, now for sun and snow. It wasn’t all misery. When I search for “married” in this town’s archives, going as far back as it will allow me, there are over 1000 mentions. Some of the houses where they lived and dreamed still stand. You can find them in old photos like this one — the records overlapping on whether this was a hotel, a general store, or both.

As All Hallow’s Eve approaches and I tell neighbors as I see them about our own headless horseman, I hope that the history helps remind us about the perseverance of this town. For all the lives lost to disease and avalanches and heartache, for the collapse of an entire industry, the crumbling and burning of buildings, the town is still here and thriving with only enough people to fill one movie theater.

During the Samhain festival where Halloween has its roots, the souls of those who had died were believed to return to visit their homes. Here, like most places, their homes are gone. But this valley remains, and they remain in it. The least we can do is nod as we pass to those remembered and those lost.

Happy Halloween.

If you’re having suicidal thoughts, you’re not alone and there is help. The Lifeline network is available 24/7 across the United States at 988. If you need emotional support, or know someone who does, all are welcome to call.

Wow. Your writing to continues to amaze.

I love all your writings, but I found this one particularly moving. Having grown up partially in a mining town (Butte MT) and living most of my adult life in the CO mountains, I am familiar with these old graveyards and stories. When I walk through one, I'm always struck by the number of infants and young children who died of what were, most likely, preventable or at least treatable conditions. And, yes, pneumonia, which used to be called "the old man's friend." Beautiful piece, Kelton.