It’s not like I didn’t warn the shipping company. “People have had us meet them at the end of the road, and that’s OK. We’re totally happy doing that. It’s icy, it’s steep, and a lot of people get stuck.” Large deliveries are often reserved for the warmer months, but I saw a deal, and it wasn’t winter when I ordered it. When the shipping company called to schedule the delivery the first time, I was clear. When they called the second time, I was explicit. And when the actual driver texted the third time, an hour away, I was exhaustive.

But I got ignored and well, they got stuck.

“Podemos ayudar?” I asked after they gave up on getting the truck up to our house and decided to carry the dresser from the intersection.

But you’re not allowed to help. It’s against the rules of the shipping company.

Once they got the dresser inside, they both leaned against the wall panting while I stood there with my stretching belly peeking out between sweatpants and a t-shirt. A useless woman ordering a dresser off the internet.

“Muy mala calle, huh?”

He laughed and nodded. I tipped him, said my thanks, and ripped the packaging open as they drove away, this time with chains on. The dresser was beautiful and like most things that make their way here, broken. I added it to the list of things to take care of and smiled ear to ear. It was perfect.

That is the benefit of a wood shop. A wooden dresser is never truly broken, only likely to be even more discounted when you email the company sending it and tell them it’s a nightmare to return and resend here, so why don’t we make this easier on everyone and just give us a little refund, and they did, and then Ben took the broken drawer to the woodshop and fixed it.

It’s always a treat to learn your own convenience.

It was a powder day on Thursday and because no one is paying me to do anything right now, I was there. I don’t know how to ski powder. We never had any in Ohio, and if we did, you had about 200 feet before you ran out of it. I grew up ramming my edges into ice, skating across the slope and backwards as I carried 3-5 year olds around the hill teaching them pizza and french fries. I can dance on skis. But I can’t ski powder. Doesn’t mean I don’t try.

So I was on the mountain and so was the avocado inside me. The fun thing about learning to ski powder is that you’ll always see someone who is also attempting to learn it, but much, much worse than you. More terrain opened on Thursday morning, and as I rode the lift up, you could see people digging through the snow like badgers, just flinging soft snow out of the way attempting to find whatever pole or ski or combination of the two they lost after an unsuccessful attempt at the run.

This would not be me. More important than any ski or pole, I had an avocado to protect. So I followed the cardinal rule of skiing pregnant: go where the other people aren’t. I skied to the next lift, to the highest terrain open, to an absolutely empty run of three miles. And then like a deer on ice I made as graceful as turns as I could, trying to find the balance between “pushing the bush” and keeping my tips up. I didn’t fall, but I didn’t — how do I put this? — look good.

After a few rounds of that, I was wrecked. I skied out of the powder and onto the groomers to properly zoom out for a moment before finding myself at the very bottom of the hill where the little ones learn. I slid into line next to a man bedecked in black behind a dad struggling to keep his two stick-footed children upright. They stumbled forward, somewhat together, as they headed toward the loading line.

“STOP!” the man next to me barked at them.

It’s a hybrid lift. Not every chair that comes swinging around for loading is in fact a chair — some of them are gondola cabins. And they were about to get clobbered by one. They all stumbled backward, the father too discombobulated to even give a nod of thanks, before hurtling his children forward to catch the next actual chair.

Once the man in black and I were seated on our chair, he apologized.

“Sorry to startle you.”

“Oh no, I loved it. And they needed it.”

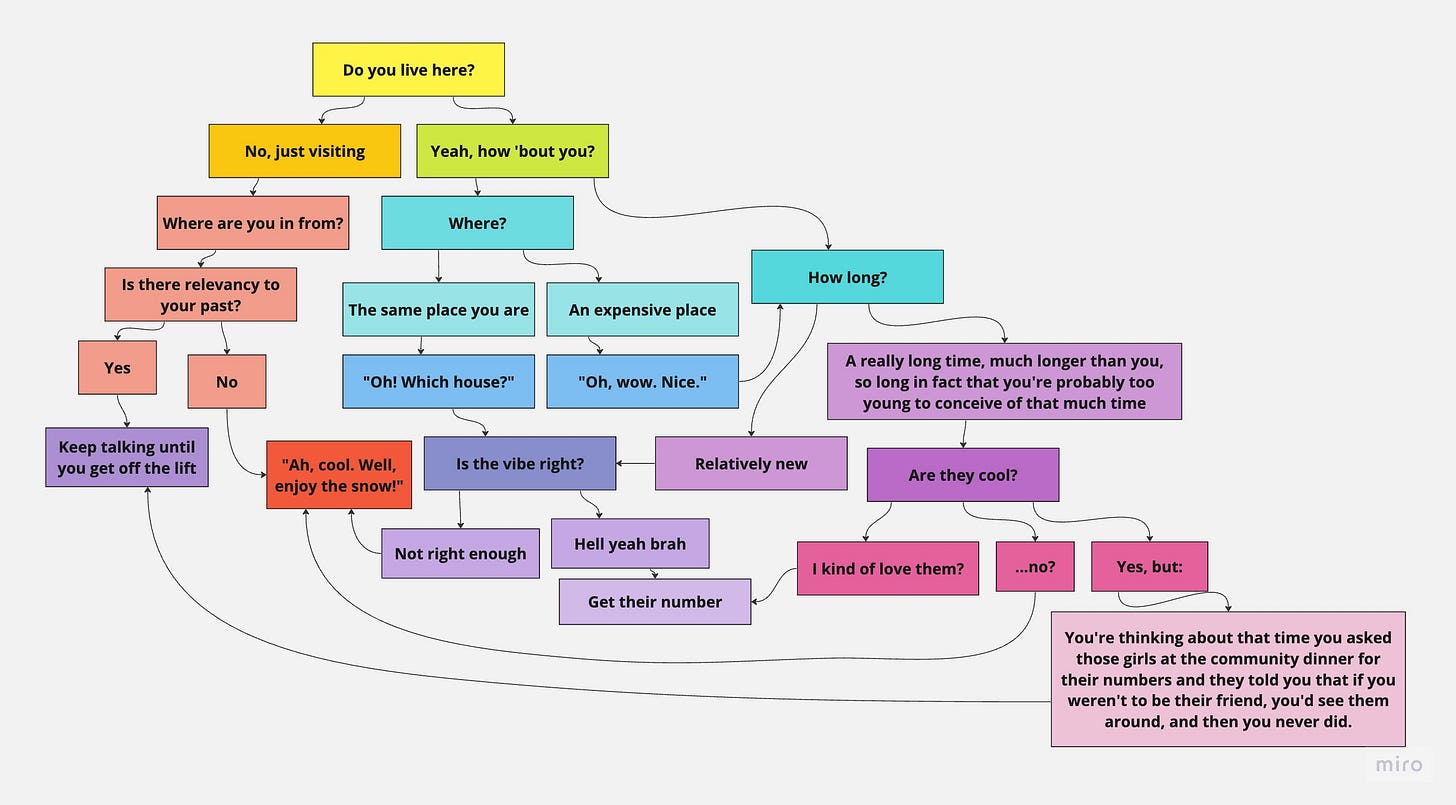

And so we began the standard lift conversation.

This is where all polite lift conversations should begin unless blatant evidence clarifies the point. Assuming a local doesn’t live here is like calling them a gaper to their face, unnecessary and rude. Giving a tourist the benefit of the doubt is flattering and generous. And so it begins.

Now we know what we’re working with. In my particular case, the man lived here, or at least lived here in the winters for many, many winters in a row. That’s enough to be a local if you're community-involved. And this man was. After introducing ourselves, he asked, “why don’t I know you?”

Well because I’m an alone-time loving writer in a cabin in the that tiny town over the ridge that everyone says is full of people with attitude. We carry on, have a nice conversation, exchange full names, and I ski off to the bathrooms like I have to do every two runs now.

We followed a common path.

So we talked until we got off the lift. We joked about how long it takes to be a local here, him saying minimum ten years. I teased in return, “harder here than New York!” though I don’t really feel that way. It’s just a thing to say to make someone smile, to keep the conversation going. I might not be a local to everyone, but I’m certainly working on it. It’s always a treat to just talk to people anyway.

“Is there a perfect mountain town for me?” That’s what Heather Hansman asks in her latest for Outside. Hansman hosted a workshop once at the library in the town over. After she wrote the book Powder Days about the future of skiing, I’ve been following her writing.

Ben and I did something similar to Hansman: after our reasons to be in a city vanished, we wanted to as well. We went on a road trip, exploring every little town we could find before we found the right one — the perfect one. There’s a reason this blog is called Shangrilogs. We found our Shangri-La in a log cabin, and not just in the house but in the town.

And maybe it’s only perfect for right now. For a good chunk of my life I felt a homesickness for the tropics that I didn’t have any inherited right to. When I finally got the chance to live there, I loved it and then I lost it. Like young love, it was what I thought I wanted, where I thought I belonged. It was the same with New York. Another place I was sure I’d belong and then so obviously did not.

A few nights ago I found myself at the town staff holiday party. Our neighbor, the mayor, was hosting. The previous mayor was there along with the town manager, members of the environmental commission and the planning & zoning commission, a few other locals who keep projects moving, and of course, my husband the clerk. The room skewed older. Some of them have lived here for 30+ years. Given our measly 2.5 years, it would be easy to dismiss us, but that group is one where I feel the most known and the most accepted.

Hansman tackled her housing search by making a Venn diagram of the four things most important to her: “people we loved nearby, easy access to the outdoors, affordable real estate, and a strong likelihood of remaining livable from a climate standpoint.” We shared her sentiments on the outdoors and affordability, but one thing that we didn’t need was people we loved close by. Instead, we hoped that other must-haves would lead us to people would love in the future: access to the arts, Wild West architecture, progressive community, and a location remote and challenging to get to.

It worked. Sitting around the table and couches, age didn’t matter. It mattered more how you felt about dirt roads and dogs. How you felt about building more housing and skiing while pregnant. Years spent didn’t count for as much here so much as how you spent them. And spent with these people, it’s been pretty easy to call this place home.

It’s always a treat to just be who you are and have that be enough.

One thing I like about the ski hill in my not-really-a-mountain-town is that pretty much anyone I ride with lives here too. If they're from out of town, they're here visiting kids/grandkids. So we'll talk more about what they do, or I do. And there'll definitely be some discussion of our respective most recent runs, and most recent powder day.

We've been here 14.5 years, not nearly long enough to be local: in a college town, having gone to high school here is a significant division point. I did live in Montana 1978-88, though, and so there's a 2-3 degrees of separation thing going. (Montana is said to be all one small town with really long streets -- at my granddaughter's birthday party yesterday, the grandma of one of the other girls knew someone from her young adulthood that my wife had known -- 300 miles away from here -- in the mid-1980s.) We're getting a lot of new people, but it kind of seems like they're mostly here not because they want to be a part of our community, but because they didn't want to be a part of the community where they lived before.

Kelton, your little town and the bigger one nearby probably isn't attracting many of the 'fleeing diversity' type of migrant, and it's not nearly as big a deal here as in some other parts of my state, but this is a non-trivial part of the 21st century West, and I sure wish it wasn't.

I’m living my “off the beaten path but not completely off the grid dream” vicariously through your exploits. The oft insatiable yearning to belong, balanced with the need to be FAR from the trappings of shallow unsatisfying relationships, is what echoes in my soul when I read your posts. Prayers for a beautifully healthy baby! I hope you have a wonderful holiday, with no chimney catastrophes!