If you didn’t read last week’s newsletter, start there where I begin the journey of learning to shut my mouth.

I kept my pedaling soft. If I put any more effort into it, I was going to pass out, clipped into the trainer sitting on the unfinished cement floor. I started with what I thought was a simple ambition: to transition my experiment with breathing through my nose to athletics. The trainer is set up in the basement, looking out through floor to ceiling windows with packing tape over them to keep the draft out. It doesn’t work. When it’s 9°F outside, it’s around 45°F in that room, 55° on a good day. This is arguably a great temperature for training indoors. I start in a sweatshirt and beanie and slowly remove layers as I warm up. But this time, the layers came off in the first three minutes.

I was riding the trainer with my mouth taped shut in an effort to actually use my nose. It started out fine.

But as I pedaled, things fell apart. It became clear that the problem wasn’t just that I didn’t breathe through my nose, but also that I didn't know how to breathe through my nose. Imagine spinning in circles with your forehead resting on the end of a bat for five minutes, then trying to pour soda from a 2-liter into a teaspoon. It’s a mess, spilling everywhere, and that is what my nose-breathing is like. One nasal inhale is a drip, the next a wave. Breathing is meant to be rhythmic, and for many of us, ideally, automatic. You’re not supposed to think about every single inhale and exhale.

But that was all I could think about. And it was obvious.

To alleviate the quiet swell of panic in my chest and the obsession with regulating my breath, I googled it:

Ah, yes, incredibly helpful. I turned to distraction instead, editing photos and videos on my phone while I pedaled. I did this for 45 minutes, or essentially up until the minute when I thought I might permanently damage something inside my head. It wasn’t just that my nose-breathing was awkward and stunted — breathing through my nose hurt. I’m not alone in this.

Seven days into this experiment, breathing gently through my nose while sitting here typing feels, at best, strange. Breathing heavily through my nose while I ramp up my heart rate feels a little like putting my brain on dry ice. My eyes, my sinuses, the whole front of my face felt like I was tattooing the inside of it. Tolerable, but genuinely uncomfortable.

If you’ve read James Nestor’s book Breath, you may recall learning about Empty Nose Syndrome, sometimes a terrible side effect of turbinate reduction, which I had, so obviously like any good anxious person, I googled the symptoms to see if I had it.

Symptoms of empty nose syndrome include:

feeling like you are suffocating

feeling that inhaled air is too dry or too cold

nasal obstruction, even though the passageways are clear

nasal bleeding

extreme dryness or crusting

lack of the sensation of breathing

feeling that too much air is entering the nose

dizziness

lack of mucus

not being able to breathe

inflammation and pain

diminished sense of taste or smell

sleep disorders, such as an inability to sleep or daytime sleepiness

I only experience three of these, and some of them are likely tied to where I live: air “feeling too cold” and nasal bleeding. The air is cold, even in the house. As I type this, I am alternating putting hands up my sweatshirt against my stomach to warm them up. And because the amount of oxygen up here at 10,000 feet is a bit slim, the air becomes drier causing blood vessels inside your nose to crack and bleed.

Despite the more persistent remnants of health anxiety tempting me into convincing myself I have ENS, I don’t. My reaction after the turbinate reduction was disbelief at what I’d been missing, not a feeling of suffocation. I often fantasize about what it would like to be in someone else’s body for a day, to feel how they experience pain and stress and exhaustion. Ben is my best example of this. Ben has never taken one of those 23andme tests, but whichever one tells you you’re born to be an athlete would surely tell him he is. He can push his body physically in ways that would push me into a mental breakdown. So obviously I’m in constant pursuit of finding a way to keep up — and breathing right could get me closer.

When humans work out, breathing through our mouths can feel instinctual — it gets rid of more carbon dioxide, but studies are beginning to suggest that tolerating higher levels of carbon dioxide in the body might actually make for higher levels of fitness.

So I wanted to try something harder than a gentle spin indoors. I went to skin up a mountain at dawn when it was 11°F.

If I thought my brain was on dry ice before, whew, skinning up a mountain while attempting to breathe through only my nose made my brain feel like a sponge that was squeezed and left for days till it contorted, losing all malleability like dead coral. But the inside of my nose was not dry. In fact, every couple minutes, I needed to stop and snot rocket onto the snow, blood included. I really sold my experiment to my compatriots, bloody snot dripping down onto my lips as I rattled off stories from Nestor’s book.

The last time I made a concerted effort to trial and error my health was when I attempted to drink the recommended amount of water every day for 10 days. I peed my pants twice, once while I was riding my bike. I actually avoid water when I can, lest I spend all night going to the bathroom. But breathing through my nose might help this. This is a little counterintuitive. After all, anyone who has spent the night sleeping with their mouth agape can attest to how dehydrating it feels — and it is, but the dehydration is not connected to the urination.

When the body sleeps, it releases the anti-diuretic hormone (ADH) to prevent us from needing to wake up to go to the bathroom. But sleep apnea (often induced by mouth breathing) changes the release of ADH. Sleep apnea strains our hearts, and the body responds by stopping ADH, so urine production resumes and our bladders fill and there I am peeing every night at 4am with dry mouth.

Never one to take things slow, there are more layers to my experiments than just taping my mouth shut while exercising.

To ritualize it: I am doing the Tibetan Rites every morning.

I need more than the physicality of my breathing to change, I need my relationship with breathing to change as well. I need to enjoy it to make it stick. And because the benefits haven’t been immediate, I need to build in a reward system. These rites feel so good that they scratch the reward itch while reinforcing the how.

To support it: I’m taking two medications to help.

I can’t breathe through my nose if the airways aren’t clear. I went to my doctor with a complaint about phlegm, and while she did recommend I read Breath, she also prescribed me a saline nasal spray along with Flonase to clear up the blockage while I retrain my airways.

To intensify it: I’m doing Wim Hof’s breathing class and cold showers.

Look, the verdict is out for me on if cold therapy actually works, but an annoying amount of people have told me it has improved their circulation, and as my hands stuffed up my sweatshirt indicate, I have very cold hands. I’m cold in general. My average body temperature is somewhere around 96.5°F, something I tracked during another forgotten health experiment.

Cold showers are part of the Wim Hof course. Wim Hof’s breathing is actually just tummo breathing, purposefully hyperventilating yourself. This is the kind of breath you can use to heat yourself. I am stressed, often, which means I am inflamed, often — and that is bad for you! But tummo breath works as a pressure release valve, not emotionally dissimilar from getting into your car and screaming as loud as you can. So I am doing the breathing and I am taking the cold showers.

Have you ever considered cold therapy? Here’s what it’s like. Please enjoy this audio clip of my first cold shower. (Also sorry: you have to click through to listen.)

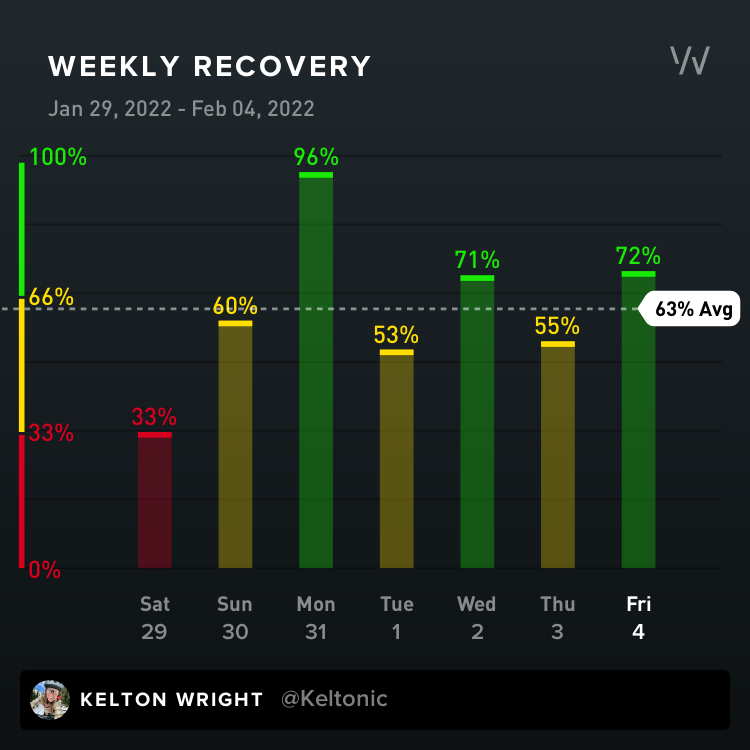

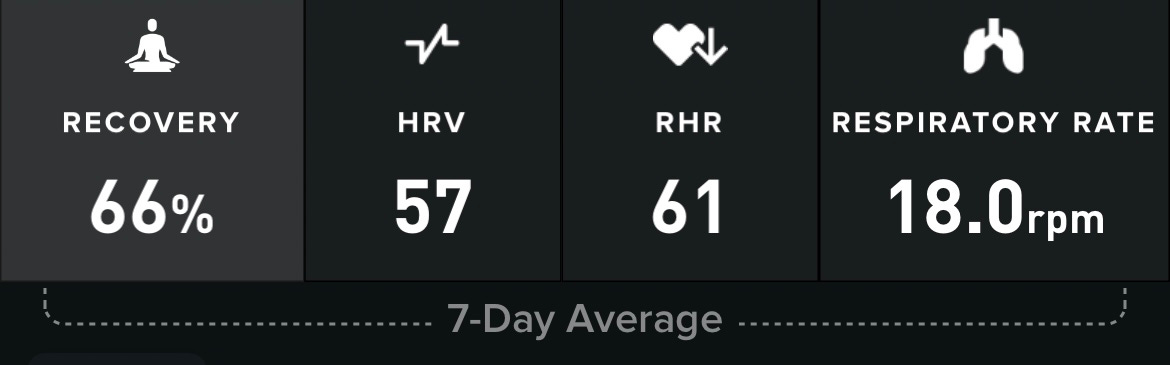

The water was at 45°F. I was able to withstand it for maybe 40 seconds? That was several days ago. On Friday, I stayed in the cold shower for eight minutes. But on Saturday, my hands were still cold when I was skiing. What I don’t know, aside from if cold therapy will work, is when. I’ll be tracking my own perception, but much of this experiment can be tracked with actual data. Welcome to my Whoop data.

Saturday is when I started incorporating nose breathing. Then I got drunk on Tuesday night, so. But I am interested to see how this changes. Here’s the week prior:

Not great.

But much of what I will be tracking is how my health and athletic performance improve overall.

Here’s a week of mouth breathing:

And here’s a week of beginning to do nasal breathing.

There are a lot of variables that go into this data: work stress, drinking, smoking weed, exercising, not exercising, etc. But my goal is to increase my Heart Rate Variability (HRV), decrease my Resting Heart Rate (RHR), and decrease my respiratory rate. And I’d like my recovery to be consistently higher.

This week, I begin actually taping my mouth shut while I sleep — after taking vitamins, putting in my retainers, and swiping on lip healing cream. A sexy routine if I ever saw one. But if breathing through my nose really does what it should (make me healthier, stronger, faster, clearer, and in general, better) then it might turn out to be pretty sexy after all.

Like you, I have a deviated septum. I've wondered if it worsened during my trials in learning how to kitesurf. [Read face plant at 100 miles per hour.] But you have inspired me to bring a healthier breathing routine into daily life and maybe even buy that book. I've been even keeping my mouth closed during meditation, but I don't know if I'm really getting enough oxygen or if tiny bits of air is snaking into my mouth as I go deep. But at least I feel relaxed. The only time I think my chest is about to explode is when I sit at my desk and try to work. Props to you for exercising! I would suffocate. PS. I did Wim Hof for all of 2020. I honestly credit the technique for staying healthy during the height of the pandemic, but I live in the Caribbean, so I had to cool down a jug of water in the freezer to get the ice shower component going. That wasn't sustainable. So, envy you! Sort of;) I can't wait to read Part III! You made me lol this morning.

Digging the fully examined life with data to boot.