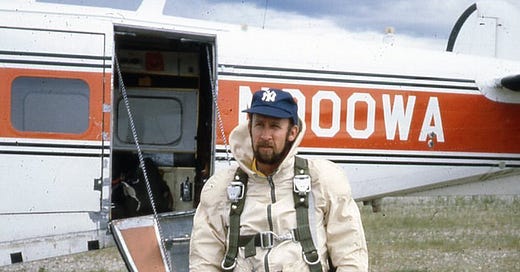

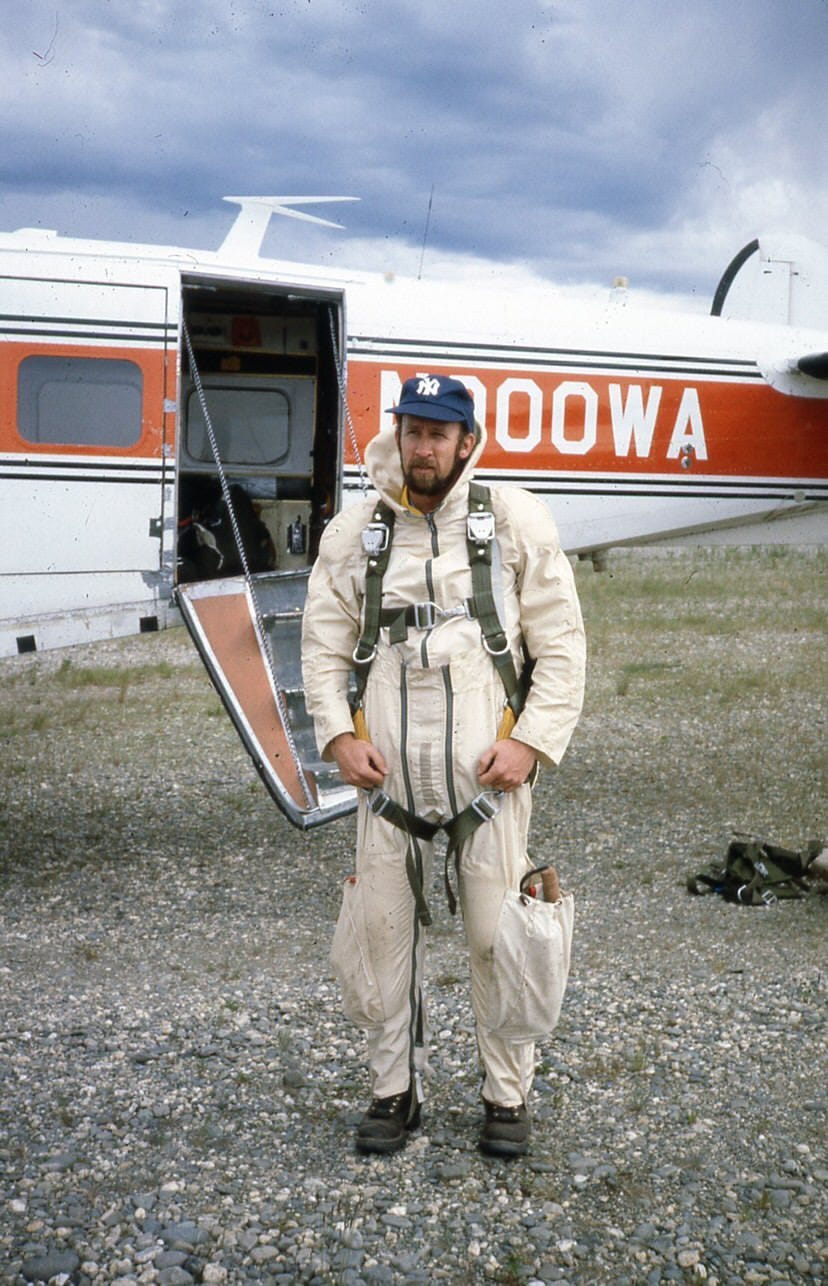

Wildfire season doesn’t exist anymore. It is now all year — as evidenced by the Marshall Fire in Boulder County this past December that destroyed over 1000 buildings, caused over $500m in damages, and burned over 6,000 acres. My dad, Clay, is a retired smokejumper, and he’s been sending me fire reports for over a decade as the places I’ve called home have become increasingly at risk. Below is a lightly edited transcript with him on smokejumping, wildfire management, points of failure, and more. It’s long, but it is worth it.

Kelton Wright: Why don't we start with just the basics? What is a smoke jumper?

Clay Wright: A smokejumper is a firefighter who arrives at fires via parachuting out of a plane. Smokejumpers handle wildfires in remote, roadless areas where either it would take too long to get a ground crew there or there's no place to land a helicopter with a helicopter crew, or it’s not safe to repel from a helicopter. There are currently seven US Forest Service Smokejumper bases and two Bureau of Land Management smokejumper bases scattered across six Western United States. The idea is to have smokejumpers available on call within less than a 30-minute window between when a fire is spotted (either by a Forest Service lookout or a patrol plane) to having somebody on the ground extinguishing that fire.

K: Tell me a little about your experience.

Clay: So the base I worked from was in McCall, Idaho and when I was there, we jumped out of DC-3s — which is the civilian designation of a C-47 military cargo plane — and de Havilland Twin Otters, a high wing twin-turbine aircraft, plus Beechcraft 99s, a smaller high-speed aircraft for getting to small fires very quickly. The advantages of the DC-3s and the Twin Otters is that they're able to fly at very low speeds. Obviously you don't want to exit a plane at very high speed and get caught in turbulence. These planes are able to fly low and slow to get you to a fire, because typically you have very small jump spots.

K: Pretend I don’t know what a jump spot is.

Clay: A jump spot is where you try to land — it’s somewhere near the fire, typically an opening that you can get down into between the trees where you aren't going to land in water or in a rock field or hang up in a tree. The idea is to drop from no more than 1500 feet elevation so that you can guide yourself in. The parachutes are steerable to a certain extent, without drifting too far from the fire or landing so far from the fire that you can't get there in a reasonable time to extinguish the flames. Because of the low altitude, there's no ripcord jumping. Everything is static-line jumping, which means you attach a line from your parachute, you hook up to a cable that runs down the length of the plane inside near the roof and when you make your exit, it automatically pulls the chute from your backpack and inflates it. So as soon as you jump, part of the chute is starting to trail out behind you and open so you immediately can reposition yourself, see where a fire is, see your orientation, and try to get into the jump spot.

K: How do you pick the spot?

Clay: The jump spot is determined by the spotter. The spotter is a smokejumper who is not going to jump on this fire. They’re in the aircraft only to be a spotter. That means once they locate the fire, the plane flies over the fire to low altitude and the spotter drops what are called streamers, which are long pieces of colored cellophane attached to a small piece of 15-gauge wire. Now, think of a stiff wire, maybe an eighth of an inch thick and about six inches long, and he drops three of these streamers when flying right over the fire and then the plane makes a circuit around. The jumper is watching how far away from the fire those streamers drift. They're simulating the fall rate of a smoke jumper so they can determine which direction the wind is coming from. You want to drop the jumpers up wind so if the wind moves them, they can move with the wind to the jump spot.

In other words, if you jumped right over the jump spot and there was a 15mph wind, by the time you got to the ground, you might be a quarter mile downwind from the fire. Once the jumpers are on the ground and have signaled to the jumpship that everyone’s OK, the aircraft prepares to make the cargo drop, which consists of stiff cardboard boxes (5’ x 5’ x 2’) attached to small chutes. Tools, sleeping bags, water, food, they’re all packed in these boxes, then the jumpship makes a pass over the jump spot very low, about 300ft with the landing gear down, flying as slow as possible, and the spotter kicks out the cargo hoping it drifts into the jump spot.

K: Sounds reliable. You mentioned earlier ground crews, helicopter crews. Can you tell me a little about when and why the different crews are called and how they work together or don't?

Clay: Well, originally the Forest Service had what are called district crews stationed on each district in a particular forest. Forests are made up of districts which are simply parts of the forest organized around a central spot, which probably has a ranger station, an airstrip, and a helicopter landing pad. The idea is to have these crews stationed in the areas where fire activity is likely so that they could get to the fire on a short term basis. Originally, before smokejumping, these crews would either walk to the fire, or they would take a pack-string with tools and walk to the fire. That's one of the reasons there are trails all through the Forest Service trail systems: they weren't built to accommodate tourists and backpackers and hikers and fishermen. They were built to provide access to fires. Trail crews would go out and do 10-day swings on these trails during the summer and clear downfall and brush and washouts, camping along the way to maintain these trails.

As the Forest Service evolved, these crews also became helitack crews, which meant there would be a helicopter station at the ranger station and they would arrive at the fire by helicopter, if possible. In other words, if there was a meadow or a flat area or some sort of an opening that a helicopter could land in, they would drop the helitack crews off there. The ground crews beyond that are what everybody calls hotshot crews. Now, hotshot crews are anywhere from a 20- to a 26-person crew. Crews are stationed in an area near an airport (typically regional, not like Denver or LAX) and the idea is to have quick access to Forest Service or BLM aircraft to be transported to a large or out-of-control fire. They fight fires that are not handled either by smokejumpers or helitack crews or district crews. In other words, they're the kind of firefighters that go to what's called project fires.

K: What’s a project fire?

Clay: Project fires are fires that get out of hand quickly, and they grow from anywhere to 100 acres, to 1,000 acres, to 10,000, to 100,000 acres, and then you have to call in these hotshot crews to build firelines around these fires. Typically, in a large fire, you might have anywhere from six to 10 to 20 of these hand crews. These crews come with all their own firefighting equipment, all their own tools. The Pulaskis, shovels, chainsaws, gas cans, emergency fire shelters, backpacks, water containers, rations, all of this. So they're immediately ready to go to a fire anywhere in the United States.

I spent three seasons on a hotshot crew and fought fire in seven of the Western states as far north as Northern Washington and as far south as Arizona and New Mexico. So those are called hotshot crews. The interregional hotshot crews that handle mostly project fires typically aren't called out for something like a 5, 10, 15 acre fire, because you don't need 20 or 26 people on a five-acre fire.

K: I recently read a book about forest fire fighting on the urban wildland interface in Boulder, and there was some confusion there about who runs what on that border land, essentially where it's both city and wildlife. Can you talk about the decision making process around who's in charge of that?

Clay: Well, that's one of the problems that arose in the last 10 or 20 years is that urban interface. The Forest Service, and it's not just the Forest Service, also the Bureau of Land Management and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. All these agencies that control federal lands have their own firefighting services. Typically, the Forest Service is the one that has the most aircraft and the most ground crews, the most district crews, the most helitack crews simply because the National Forests are typically (and obviously) on land that is forested and therefore that's where the fires typically are harder to fight. The BLM also has fire crews, but typically those are range fires. Range fires, when they get out of control, you can bring in bulldozers and cut large firelines at a high rate and there aren't heavy-load, long burning fuels that cause the fire to get out of control.

But the urban interface is a problem because there's sometimes a question: a demarcation as to who has priority over a fire like that. The problem too is that in urban areas, obviously you have fire departments, whether it's a city fire department or a county fire department that handles those sorts of fires, but the urban interface spreads more and more into forested areas. It becomes a problem, "Well, who has priority and who do we call initially on these fires?" One of the problems with that is there was a fire that was on a power company right-of-way two years ago in California that was started by a transformer fire from high tension lines. The power company sent a crew out there to see what the problem was, they saw it was a spark from a transformer that was malfunctioning and it had started a fire, but they decided the fire was going to burn into a remote area and therefore it wasn't immediately necessary to call any crews on that.

Then it becomes an issue of, "Well, who should make the decision on that?" The power company is not in charge of fighting fire. They should have immediately notified a cognizant fire agency, whether it was a fire department or the Forest Service, and let them know that there was a fire in that area. So a lot of times-

K: Do you know what fire that was?

Clay: No, I don't know what fire that was called, but it was something to do with the power line fire.

K: Yeah. That feels like almost all California fires.

Clay: Right. Who's in control of this? There was a fire north of Lake Tahoe in one of the wilderness areas just last year, but fire management flew over it and decided that since it was burning in a wilderness area, and it was a rocky area, that it didn't need to be manned, that it would burn itself out. So they decided not to notify the smokejumpers. The smokejumpers were approximately 30 minutes away by aircraft to control that fire, the California Redding base in Northern California. But they decided not to notify them of the fire and would just monitor it every couple of days. Well, that five-acre fire turned into close to a 50,000-acre fire and in the writeup afterwards, one of the people that made the decision not to call the smokejumper said there were no crews available.

It has been pointed out that there were smokejumper crews readily available and willing to man that fire and this has turned into congressional inquiry that's ongoing now as to why that fire wasn't manned and who made the decision not to man it. So even though it wasn't in the urban interface, that's the sort of problems you run into when there's an overlapping control of who decides how and when and where to man fires. In the forest interface too, it becomes a problem where if you have a subdivision, say, in a forested area, a lot of these don't have adequate water systems in terms of things like fire hydrants, where the city or county fire trucks efficiently fill up and continue to fight the fire. But it is also not the scenario where you would call smokejumpers in. You can't call aerial parachutes into a subdivision area, and if you get 20-person crews in there, then there's a question: are we structure fighting or are we trying to control a forest fire via cutting firelines? Because hotshot interregional crews are not trained to do the former and fire departments are not trained to do the latter.

So right now there is a quandary, there isn't a clear solution as to what the answer is now in the urban interface, because you have an overlapping responsibility and a determination of what kind of fire is this. Is this an urban structure fire? Or is this a wildland fire? Because there's two completely different approaches and multiple different agencies responsible for either attacking wildfire or attacking urban fires.

K: Can you talk a little about prescribed burns and what the history of them with the Forest Service is and why sometimes they can get out of control like they recently did in Ouray, Colorado and in New Mexico?

Clay: Yeah. When the initial fire attack and fire control started, it all goes back to the great fire of 1910 in Northern Idaho. A fire started in Northern Idaho and there really wasn't (at that time) there wasn't any Forest Service, there weren't any dedicated crews. There were really only lumberjacks in the forest. When there was a forest fire, thos lumberjacks would try to put it out, obviously to save the timber and save their livelihood. Well, this fire that started in Northern Idaho was a lightning strike, but then it was followed by very low humidity and very high winds and the fire quickly got out of control. It burned for five or six days, very hot, very fast moving, and in the end burned 10 million acres of lumber through Northern Idaho and into Montana. It killed, I think, something like 25 or 26 people. It trapped a train with passengers in the fire and they were only able to survive by going into a long tunnel and parking the train there.

It also completely burned two small lumber towns in Northern Idaho along the railroad right-of-way. This is what prompted the Forest Service to start hiring designated firefighters. Shortly thereafter, it began the idea of “we have to control forest fires. We can't let forest fires do this anymore. We can't let them destroy towns. We can't let them kill people. We can't let them destroy timberland.” So the idea of firefighting slowly became “everything out by 10 o'clock in the morning.”

Immediately after this fire, the Forest Service not only began the process of hiring designated firefighters, but they also started building lookouts. At one point in the Northwest — Montana, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington — there were over 340 separate lookouts on mountain peaks to watch for fire, the idea being to catch fires while they're extremely small.

A lookout spotted a fire, called into a radio dispatch, or by a hand cranked telephone system, and the ranger station would immediately send out crews walking to the fire with hand tools to get a line around the fire, put it out, cut down any trees, and control the fire by 10 o'clock the next morning. Well, this went on for many years and then of course we got the advent of the first smokejumpers during World War II. After the first two smokejumpers jumped a fire, it showed that they could get on a fire quickly and could control small fires. So that was the beginning of the smokejumper era with more and more bases, more aircraft, more hires. Then after the Korean War, the advent of helicopters was used in fighting fires, both for getting people to fires and doing water drops with buckets on fires.

That evolved slowly into using retardant planes, planes that are filled with a mixture of water and something that's called Phos-Chek. It's the red retardant you see being dropped on fires and it also serves as a fertilizer. So the idea is you drop this retardant ahead of a fire, it hugely increases the humidity, it sticks to the foliage and keeps the water in place on the foliage, therefore either slowing down or stopping the fire. When the fire is gone and the humidity evaporates, it turns into fertilizer so it doesn't harm the forest floor. So it's slowly evolved into a multi approach like that.

But somewhere along the line, fires started getting bigger and fires started getting more and more frequent. The problem is, of course, more and more people started going into the woods. Initially, probably 80% of these fires were lightning strike fires. They were natural fires caused by lightning storms moving through the forest, which is extremely common in the Pacific Northwest and the inner mountain states. But as the population grew, more and more of the fires started becoming man-made, particularly in the areas of high use in California and Arizona and New Mexico and areas around national parks. So the fires became more and more frequent, requiring more and more suppression efforts, requiring larger and larger budgets for the fire suppression. With climate change, gradually the fire season became longer and longer, the snow melt started early in the spring, the snows came later in the fall, humidity decreased, rainfall decreased, so the fires were getting harder and harder to get a handle even when they were small.

Forest ecologists then began to look at the forest floor and at the old growth forest. They looked at burn scars and realized there were very few places in the coniferous forest that hadn't been burned at some point in time. In fact, one of the species, lodgepole pine, is called a fire climax vegetation. The pine cones will not open and release their seeds unless there's a fire. So obviously it's a species that is extremely adapted to wildfire. It has learned that the best way for it to propagate, since they don't grow as big or as tall is the fir trees therefore they can be shaded out by the canopy of those trees, but when those trees are destroyed by a fire, it opens the cones of the lodgepole, the fire provides fertilizer in this soil, the tree canopy is gone and lodgepole pine flourishes.

As more and more people in the Forest Service and the BLM and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, all the firefighting agencies, started to come around to the belief that maybe fire was part of the natural landscape in the forest, they looked at it and said, "Well, maybe we've fought fire too long and we've now built up the fuels too high where we need to help nature and to start burning some of these not in the height of the fire season when they'd be uncontrolled, but in areas of high humidity or early season or late season, cold crisp mornings, below zero temperatures at night.” They wanted to burn off the ladder fuels, which are the fuels that take the fire from the ground, pine needles duff, up through brush, up through the young immature trees and start reaching the branches and the mature trees and therefore eventually burn all the trees with crown fires and ground fires and heavy fuels.

So the idea of a controlled or prescribed burn is to burn off those ladder fuels, not affect the mature trees whose branches start at a higher level, and then who have thick bark around the base of the trees and clear out that debris so that if a fire does start, it stays low, doesn't burn hot, moves through quickly and doesn't affect the mature trees. The problem is, sometimes firefighters like myself think that controlled burn is an oxymoron because they specify an area for a controlled burn, but that control is an illusion. The fire doesn't know when it's reached the edge of that predesignated area and can easily spill over to areas that are not part of the prescribed burn.

Secondly, conditions change quickly when you're in the forest. Two of the largest wildfires in the history of New Mexico, which are out of control as of this date and are burning a combined 400,000+ acres, were started by prescribed burns. So sometimes the philosophy is “we've gone too long with letting the forest build up of these fuels”, but the flip side of that is we have only had efficient firefighting since the 1950s. By efficient, I mean not people walking to fires or taking a pack string of fires. I mean smokejumpers and helicopters and aerial retardant planes. So we've only been effectively putting out fires for about 70 years. The boreal forest has been there for hundreds of thousands of years, so the flip side is that we've done too much firefighting in the forests, and they are now overburdened with fuels. The flip side of that is “do we really think we've changed the ecosphere in 75 years that took hundreds of thousands of years to develop?”

K: That's a pretty good point. Could you talk a little about the state of smoke jumping today? Obviously you touched on climate change and we have more fires than ever now that affect humans' lives. What is the state doing and is it enough?

Clay: Well, smokejumping still exists, pretty much the same as it did back in the '60s, '70s, '80s, '90s, except for the fact they closed some of the smaller spike bases for reasons of efficiency. Unfortunately, the Forest Service budget has been cut for decades. The Forest Service doesn't have nearly as many firefighting personnel or firefighting resources as it did back in the 1960s, '70s and '80s. Many of the district crews that were stationed through forests no longer exist. Those stations have been closed down. There's no firefighting personnel, there's no helicopters, there's no trail crews, there's no stock available for trail crews. So the resources have gone steadily down. At the same time, we've cut way back in the number of lookouts. Once again, in an effort to save money. So now vast areas of forest are covered by patrol planes.

Lookouts would immediately spot a fire either when it started during a night thunderstorm or first thing in the morning when they spotted the smoke. The fire would be identified, the location would be transmitted and a decision could be made how and when to staff that fire. With patrol planes, sometimes one patrol plane is assigned to monitor hundreds of square miles. By the time they get to one end of the forest, a fire could have been burning for six or eight hours and instead of being one acre, it could be 30 or 40 acres by the time the fire is spotted. So part of it is a huge decrease in funding and resources. The second is there are more and more what's called “let burn” areas, particularly in wilderness areas with the philosophy being, once again, that fire is part of the natural landscape and as long as it's in a wilderness area, it's not threatening the urban interface, it's not threatening farms, homesteads, cabins. It's just let burn and let it burn itself out.

Now, the problem going back again to the change in fire seasons, back when the forest burned on a regular basis, there were two things. One, there weren't recreationalists in the forest and second, the summer fire season was much shorter, the humidity was much higher, typical daytime temperatures were lower. So fires, when they started naturally, didn't tend to turn into huge conflagrations of millions of acres running out of control. They typically were low temperature, low spreading, slow burning fires. But now we're in an era of lower humidities, higher temperatures, longer fire seasons and the “let burn” policy sometimes almost seems like “let it burn until we realize that it's gotten just completely out of control, is not going to be contained in the wilderness area, and now we have to start throwing resources at it.”

The philosophy of “let burn” is still in place and still working sometimes and not working other times. Another thing that's changed in addition with the huge decrease in the number of crews and the locations where crews are staffed is a safety aspect has changed a great deal. Back before the turn of the century, when you got on a fire, whether it was a small two-man fire or whether it was a project fire of hundreds and thousands of acres, you stayed on that fire and you worked, at worst case, around the clock and, not worst case, 14 to 16 hour days every day of the week, sometimes for weeks on end until that fire was contained. Also, we would jump into what are now called “hazardous areas”, e.g., steep mountain breaks, rocky areas, exposed areas with high wind, and difficult terrain.

The idea was if there's a jump spot anywhere, an opening 50 feet across, a meadow, an open hillside with some sagebrush, that you would jump the fire. Now they do not jump those fires. They do not jump the famous Salmon River breaks in Idaho. They don't jump anything with a wind speed over 15 miles an hour. Secondly, no crew, no firefighter can work more than 14 hours per day and no firefighter can be on fires, whether one fire or successive fires, more than 14 days in a row without having days off. So you can imagine the situation where it's a bad fire season, the Forest Service is running low on resources, they have to give a crew a break after 14 days, but there's no crew to step in to replace that crew. So there's two sides to the safety issue.

One, yes, the most important thing about fires is avoiding human casualties, whether that be firefighters or civilians or recreationalists or homeowners, but by going to the extent that Forest Service has, at the same time, reducing the number of available firefighting personnel, it becomes a catch-22 for putting out these ever increasing number, size and temperature of these fires. We don't attack it as aggressively and we don't have the resources to attack it aggressively as we did before the turn of the century.

K: Oh well, that's depressing.

Clay: Well, that's one of the things that the public generally doesn't know. They hear the information about fire seasons are extending, they hear the information that fires are burning hotter and longer, that humidities are dropping, that temperatures are increasing in the summer, and they hear the information about the urban wildland interface, where more and more people are building summer homes or year round homes, enforcement area, but they don't hear at the same time the firefighting agencies, particularly the federal firefighting agencies, do not have anywhere near the resources available that they've had in the past to control these fires.

K: Yeah. All right, let's go for a hyper local scenario. All right. So obviously you know my valley. You know our high winds generally blow west to east, which is towards my house, towards the pass road, and that there's about 200 yards of open space between the forest on either side, and then there's the tree line maybe about a thousand feet higher than us. If a fire was started in the canyon on the way into this town and the winds were blowing toward us, would we stay in the basement? Would we hose down the house? Or would we throw the pets in the truck and head over the pass?

Clay: Well, I know you know there’s no one set answer to that question, because you could take it to one extreme and the other. One, a fire started down the canyon, it jumped the road, the road is closed, you can't go out that way. But the temperature is in the low 60s, the winds are less than 10 miles an hour, humidity is high, and it is moving toward you but not at a pace where you couldn't either outrun or out walk it. Then you would say, "Okay, let's just be safe. We don't have any forests near us. We know there's just grass around there. Let's wet down some of the flammable areas." If you have a shingle roof or a shake roof or you have firewood stored around the house or there's dry grass around the house, you’d wet that all down. It wouldn't be necessary to go because you guys are not near a heavy fuel load. You're simply near grass where you are.

It's easy to control a fire in grass, even when it's slowly spreading. A hose, a sprinkler system, a few people with shovels and pulaskis, rakes. Just clearing a six-foot-wide path down to the dirt? That will stop a grass fire. On the other hand, if you have a conflagration heading your way, if the temperature's in the 80s, humidity is below 15%, the wind's blowing 40 miles an hour and the fire is spotting, which means it's jumping ahead of the fire and starting spot fires before the main fire even catches up to it, then it's time to evacuate because those embers, hot embers, can carry for hundreds of yards. You could have those landing on your roof and not even realize it. A hot ember lands on your roof from a 40-mile-an-hour wind, it's not going to go out. It's just going to get hotter until it catches something that's flammable. In that case, the other end of the scenario, yeah, it's time to pack up the pets or whatever you can grab and get out.

K: This is why our town mandates metal roofs. Are you so glad we don't live in Topanga anymore?

Clay: Oh, yeah. One of these days Topanga is going to burn to the ground.

K: Yeah. Topanga is a real tinder box. They better have real good fire insurance there.

Clay: Yeah. It's not a matter of if, it's a matter of when with that community. It's just the dryness, the location, the people, the Santa Ana winds, the difficulty of getting firefighting equipment in there. No, it's a conflagration waiting to happen.

K: Is there anything I missed? Anything else you think is worth noting?

Clay: Well, this term as in firefighters, there's kind of a hierarchy in firefighting with the federal agencies. Typically, the progression was you get a job on a district crew as what's called a forestry technician and you're taught the basics of firefighting. What the tools are, how to dig a fireline, how to operate a chainsaw and from a safety aspect, how to open your fire shelter, which is essentially a aluminum reflective pop tent that you put over you and hope the fire burns over you quickly before you're roasted. We used to joke that it comes with an apple in the bag, so you put the tent over you and put the apple in your mouth so you're completely done by the time they find you roasting.

K: Charming.

Clay: So you start out as a district firefighter. You may get on a few fires during the summer. They're typically small fires. A lot of times there'll be a fire in your district, the smokejumpers will jump it, and once they get a line around it and get it controlled, they'll turn it over to the district crew to do the mop up and get rid of hot spots and make sure there's no roots burning, make sure everything is cold before they leave.

When you get that kind of experience, the next step up is to either a helitack crew or a hotshot crew. For helitack crews, their main focus is to fight fire. Now, they're put on other projects during the summer like all firefighters are, but if there's no fires going on, you're clearing brush, you're building fence, you're painting buildings, you're sharpening and maintaining tools. Sometimes you're going behind where it's been logged and they like to call it clearing and stacking the brush, but firefighters call it stacking sticks. In other words, go out into the forest and do something.

The next step really is onto a hotshot interregional crew where you're assumed to have fire experience. They'll go over what it's like to build fire line with a 20-person crew where you'll have the two sets of chainsaw crews out front where there's someone running the chainsaw and someone else that's carrying the gas and throwing brush or limbs aside as the person with the chainsaw is cutting it. They're clearing a path and the heavy fuels and the ladder fuels, and then behind them are people cutting with pulaskis that are getting up the small brush, cutting down to the dirt.

Then behind them, you have people with McClouds or shovels scraping down to the bare dirt. So you're making a fire line that's like six feet wide where there's nothing that can carry the fire up above the line. In other words, no limbs reaching across the fire line or trees leaning across the fire line. At the base level, down on the ground, it's scraped down to the ground, the soil or rock so there's no flammable fuels to carry across on the ground. So they teach you how to build that. Each person on the crew has assigned duty as you're building this line. So when you start the line, you're looking at just a forest out ahead of the fire and when you look behind you, there's a clear tunnel of nothing but bare dirt, six feet wide.

The pinnacle of firefighting is the smokejumpers and the reason I say that is because-

Maggie Wright (my mom, former backcountry ranger and wildlife biologist): [inaudible heckling]

Clay: There's that background noise — is because smokejumpers won't accept anybody that doesn't have considerable firefighting experience. Since there's usually hundreds of applicants for maybe a handful of positions at each smokejumper base, they can pick the cream of the crop in terms of fire experience. So for example, by the time I became a smoke jumper, I had two years on a district helitack crew, one season as a fire lookout and three seasons on an interregional firefighting crew. I had been on something like 40 fires already by the time I became a smokejumper. So that's the kind of experience they're looking for. They want to teach you how to jump, how to exit the plane, how to roll, how to handle your parachute and all of that, but they don't want to teach you how to fight fire. They're assuming you already know everything about fighting fire.

So the goal there is just to teach you how to jump safely on a fire. Of course, you go through a training program that weeds out a lot of applicants. It's extremely physical because the final test is often on these fires when you jump and the fire is out, the only way to get back to base is either to pack up all of your gear and walk to a trailhead where they might be able to send a trail crew with stock out to pick you up, or if there's a river nearby that they can take jet boats up, you can walk to the river and get picked up.

Sometimes if you're lucky, they'll let you cut a helispot, an opening for a helicopter to come in and they'll send a helicopter, but that's frowned upon because you have to cut down live timber to make the helispot if there isn't an open flat meadow already. So typically you have to pack up all your gear, which consists of your jumpsuit, your parachute, your reserve parachute, your helmet, your firefighting gear, your water containers, anything that you cooked with…

Maggie: The six pack of beer.

Clay: ...Your chainsaws, your crosscut saws if you're in a wilderness area, because you can't use a chainsaw in a wilderness area, and you have to put that all under your back and walk on a trail or bush whacking to a trail or down steep slopes, cross country. The average pack weighs about 125 pounds and these are soft packs. The soft pack rolls up and fits into a leg pocket in your jumpsuit when you jump, so obviously you're not jumping with an aluminum frame pack. So if you can imagine what it's like to carry 120, 125 pounds in a soft pack, you can't stand up.

It's the worst part of the job. It's called the packout and it's the absolute worst part of the job. A lot of smokejumpers in the lower 48 after a couple or three seasons of smokejumping went to Alaska because Alaska's the land of no packouts. Because typically you're jumping a fire scores, if not hundreds, of miles from any road or river or town or anything. So 90% of the time they have to send a helicopter to pick you up, because there's no way to get back from the fire.

K: Wow.

Clay: Typically that's one of the big things that weeds out trainees is they take you out about four and a half or five miles from the jump base and you get all of your gear together, you have to pack it into the pack and then you have to put it on your back and you have to walk back to the base. It's not walking on a trail or walking on a road. They plot out a course that requires you to wade streams, to go uphill, to go downhill, to fight through brush, to get over a downfall because you're trying to create actual conditions. So a lot of people get weeded out in that part of it. So you can see why there's two reasons that the smoke jumpers are kind of considered the pinnacle of firefighting, because you not only have to have a great deal of experience, but you have to have a great deal of physical stamina to be able to do the job and then carry all of this gear out after fighting fire for two or three 16 hour days.

K: Wow. Amazing. Well, I think this answers all of my questions. Mom, is there anything you'd like to add about smokejumpers?

Clay: Here comes some smart answers.

Maggie: You want to hear a funny story?

K: I do.

Maggie: When I was a ranger at Burgdorf, I was listening over the Forest Service radio and all of a sudden I hear somebody jumping a fire and then next thing it's your dad talking on the radio and he's talking about telling KOD72, which was the McCall Dispatch Office, and he's telling him, "Yeah, the fire's rolling out. We're going to be here for a while." At the same time I could hear a pop—

Clay: Imagined.

Maggie: Not imagined! —of a can of beer because they would take their personal pack-

Clay: Gear bag.

Maggie: Their “gear” bags, and instead of putting gear in there, there would be a six pack of beer in there and I could hear it over the radio. So when he got off the fire, I was like, "You and Bob were just sitting there drinking beer, milking that fire, weren't you?" He was like, I was not, but that's what they were doing. They were working so hard. Weren’t you, hunny?

Clay: Yeah. Kelton, there's a little note on that. As part of your jump equipment, you have what's called a personal gear bag. It's really only about 14 by 14 by maybe 10 inches deep, and it's a rugged little pack. I don't want to call it a pack because what it does is it attaches two by two carabiners, like clips, to your jumpsuit below your reserve parachute. So in the front of you got your reserve kind of on your chest and below that you're hooked into your personal gear bag. Now you can put in there whatever you want, you can put in a rain tarp—

K: Is that what we're calling beer now?

Clay: Alright, smart ass. You could put in a parka for cold nights, you could put in extra food you wanted, if you didn't want to eat C-rations—

Maggie: Or you could be a smokejumper and need beer.

Clay: Yeah. The rumor was some guys put alcohol in there, but that's just a rumor. Oh, aslo, as a footnote, one of the little interesting things in this, when I talk about a Pulaski, which is one of the tools for fighting fire, in the big burn, that 10 million acre fire in Northern Idaho, there was one guy who was working for the Forest Service that saved like a crew of 60 guys who were just guys they rounded up to fight the fire by going into an old mining tunnel when the fire burned over, and out of something like 60 people, only two people died. The tool that he designed to fight fire, which is like a grub hole on one end and an ax blade on the other was named after him and is called a Pulaski and it's been a standard firefighting issue tool since before World War II. Still in use and named after this guy who saved all of those people in the big burn.

K: Edward Crockett Pulaski. That's pretty cool.

Clay: He's buried up near Kellogg, Idaho and there's a little memorial to him up there.

K: He looks pretty handsome. Mom, you should Google him.

Clay: Well, he was a firefighter.

Maggie: Oh God. That's another thing.

K: All right, all right. I think we got all the jokes we need. All right. I love you guys.

Maggie: Love you, too.

Clay: Love you, too. Take care, sweetie.

Happy Father’s Day, Dad. (Dun, dun, da-dun, da-da-da dun da-dun.)

Fascinating interview!

Your dad is a badass! Great interview. You mentioned Topanga being a fire trap. Up north, I worry about Mill Valley & the parts of the Oakland Hills that didn’t burn in the 1991 firestorm. Here in CO at least aspen groves are less flammable than distressed pine. I was running around Monarch Pass yesterday & grateful for the rain as there’s so much dead pine there, it’s highly flammable in dry weather. Pam Houston’s memoir Deep Creek about her ranch in Creede does a deep dive into living through a fire there several years ago—worth reading.