Everyone is saying it, quietly, hopefully: this winter is going to be a beast. Some sparkle when they say it, their skis waxed and ready. Others, more ominously, an eye to the horizon, noticeably wary of the dangers winter can bring. The accidents, the avalanches, the search and rescues — the search and recovers. But the energy is palpable as the sporting goods stores clear out summer gear to make way for the bulk and puff of winter. At home, I’m not clearing out — I’m filling in.

Colorado is gearing up for a third year of a building La Niña weather pattern, determined by the surface temperatures in the central and east-central Pacific Ocean. And right now, the temperatures are the coolest seen since 2010. That season delivered resorts like Breckenridge a snowfall at 80% above normal. Many Colorado mountains saw upwards of 500 inches that year — over 40 feet of snow.

Last winter was weak, struggling to reach 200 inches of the revered white stuff at our local ski area. But even with minimal snow, it still managed to snow inside. Through the gaps in the windows, around the doors, through the logs, and just about anywhere else a little frozen water with a breeze could slink through. Many mornings were spent putting on wool socks, slippers, base layers, fleece pants, flannels, sweaters, puffies, beanies, and fingerless gloves just to sit down at the computer in a house hovering around 45°F/7°C.

But not this year.

When I first toured this house in late January of 2021, it did not keep secrets. It was happy to tell you about its leaks and gaps. Space heaters in every room. Cardboard over the windows. Towels rolled up at the base of every door. Every corner offered its own makeshift attempt at preserving warmth, a reminder of winters endured and a threat of winters to come. In the nooks and crannies between logs, you could find old newspaper, cardboard, spray foam, all desperately trying to keep what was outside, outside.

Then, I was merely dating this cabin. Now, this pile of logs and I share a long term contract, to have and to hold me and my stuff. And when you move in with someone, you learn a few things. That’s what I wanted: to learn how this house stood up to winter. What I learned is that it didn’t. Winter is a bully and this cabin was tough, but it took a thrashing in every storm. It needed help.

We’re in a full scribe cabin. That means the logs stack on top of each, with the bottom of each log carved out to sit tightly on the log below – but logs change. They warp, twist, shrink, and they have no shame in doing so not only on top of each other, but around windows and doors too. Little gaps in the logs are normal, and if wind isn’t the devil up your spine, little gaps might not be a big deal. Here, however, the local joke is to have t-shirts made that say “This town blows” because of the relentless and unnerving winds. Winds that snake up your pant leg and steal things from your yard, lashing your face with your own hair. The winds here tempt a woman to go bald. At 10,000 feet, the winds are in charge. So those gaps in the logs are more like airhorns. They make their presence known.

Look at this cabin:

Notice that between each log, there’s actually a line of “mortar.” This material is called chinking, and it’s a type of sealant that moves and stretches with the logs, but most importantly, seals. Chinking a cabin used to be an ordeal. You had to hand mix the materials and painstakingly guarantee it was actually tight to the logs with no air pockets — a difficult thing to do given the material had no elasticity. Now, things can move a little faster. The products last longer, go on easier, and bend with the logs.

The logs in my cabin are massive, with r-values reaching 19-21. If you’re not familiar with an r-value, it’s the rating at which a space is insulated — the “r” stands for resistance, referring to the material’s ability to resist thermal loss. But the r-value doesn’t matter if the logs aren’t sealed. And these logs have never been sealed. Which is where the mortar comes in.

We went with a product called Log Jam, available in both tubs and caulk tubes. We went with 42 tubes because look what we also got:

This battery-powered caulk gun made beading the Log Jam much, much easier. Once you pipe the beading between the logs, you follow it with a damp 1-inch sponge brush to seal the material against the logs, then follow with a damp rag to clean up edges and residue. The limits of using Log Jam are, for us, weather related. It cannot be applied in direct sunlight, it must be above 40°F, and it needs to be dry. In most places, this is achievable, but here, where it goes from monsoon season directly to snow, we had about a two-week window to seal the whole house. And on top of that, we couldn’t begin the process until we stained the entire house. Oh, and just for fun, we decided to paint the exterior plaster at the same time. Fun!

The house has plaster on the second floor on three sides. Two sides are a moody mauve and one side a flat gray. We went with “white white” for our Log Jam sealant color and Bavarian Cream for the plaster. It’s not like Bavarian Cream was the perfect color, but there were 40 some whites to choose from and I liked the name. Between rain showers, nearly every log was stained and sealed, and the paint went up unbelievably fast. You can see the process and the final look here.

The winds came in at punishing speeds on Friday, and I put my hand to all the old whistle gaps and … nothing. Stillness. Not a breeze. I’ve never wanted it to snow so badly. In the end, all of this winterizing is to protect ourselves and our home. To keep what’s out, out. But sometimes, what’s outside has to come in. Sometimes, what’s outside needs your help.

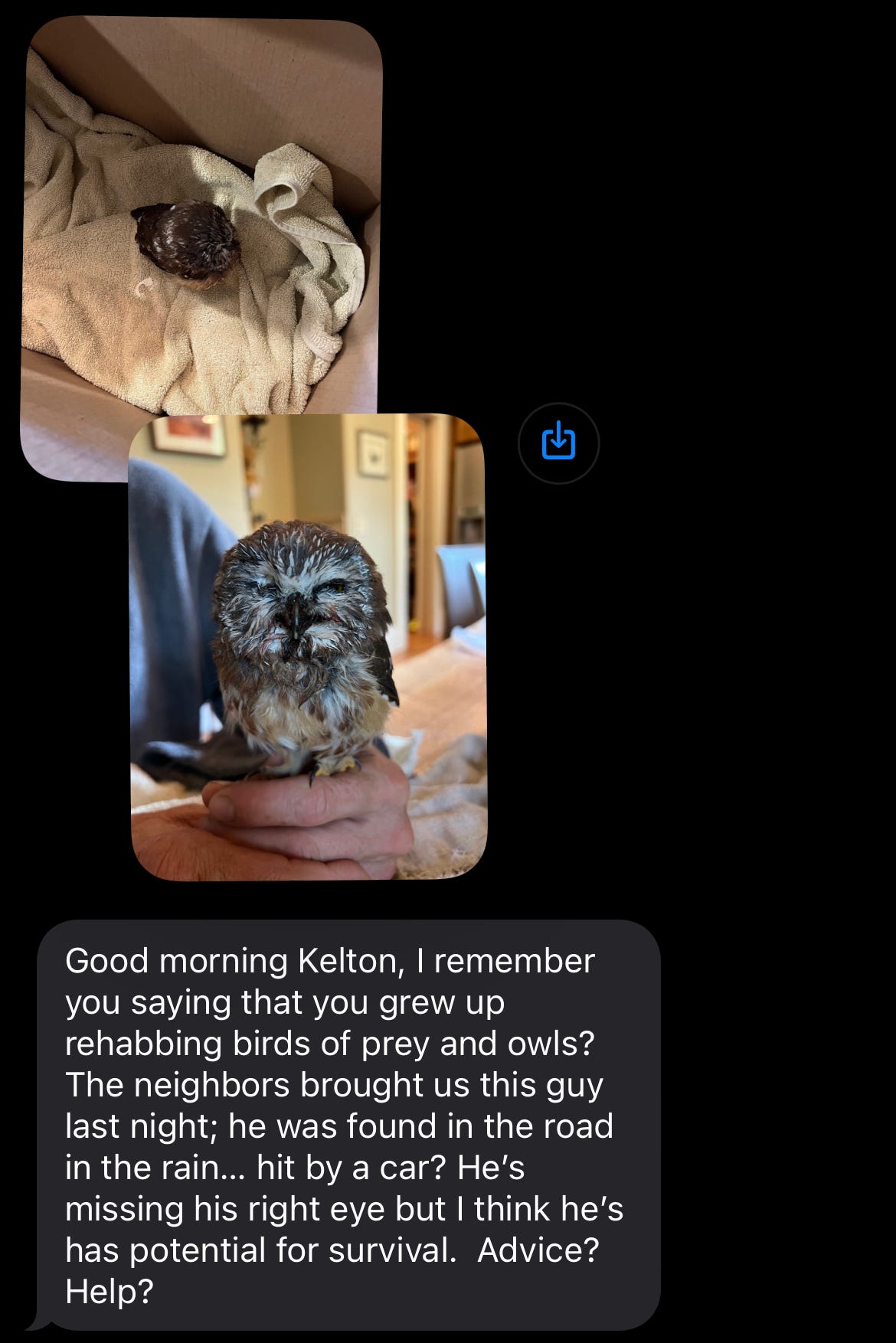

I was in the middle of working on this newsletter when I got a text message from a neighbor.

That is an adult saw-whet owl. They’re about 7-8 inches in length, and only 3.6 ounces. They can be found all over North American forests, and my god are they charming. She was soaked when good samaritans found her on the road, likely hit by another car. Owls, when hunting, are laser-focused on their prey, so it’s likely this owl dove into the car’s path, aiming for something much, much smaller.

If you recover an injured wild animal, the best thing, always, is to take it to a wildlife clinic. But because we live in the middle of nowhere, the closest clinic is some 3 hours away — and they were already closed by the time this little owl made it to me. So I did the next best thing: I called my mom. My mom, prior to retiring, was a wildlife biologist with a focus on birds of prey. I grew up hand-feeding owls and nursing them back to health. But I was 10. I needed a refresher.

Some basics: for birds of prey, keep them in a dark box with a flat towel. A bunched towel may seem like it offers more warmth, but it really offers more opportunities to get their talons stuck. The box should be in a dark, warm, contained room. This owl is in my guest room. Why a contained room? Because in the morning, if she’s showing signs of recovery, she’ll get to do a test flight in the room before full release.

Once you’ve set up the owl’s suite, it’s time for some room service. Because there was trauma, this owl needs ibuprofen to reduce the swelling. I crushed one Advil and stirred it into a small glass of water. Next, I cleaned out a pipette from some hair oil to use as a syringe. Slowly but surely, I fed her water from the pipette. The tiny bits of ibuprofen in the water ensure she gets enough medicine, but not too much. She might have a concussion or internal swelling, and this can help. Then, food. Saw-whet owls are carnivores, but they can’t digest beef, so I’ve cut a slice of turkey into tiny bits and coated it with electrolytes. (Again, this is all wildlife clinic recommended — I was also like, “electrolytes?”)

As I write this, it’s 8:30pm on Saturday — a riveting Saturday night if there ever was one. The owl is in her box in her room, awaiting her next food delivery. The pets are sitting outside the guest room door, aware someone new is in the house. All day, I struggled with this newsletter. How does one make sealant interesting? How can I expand on preparing a home for winter when for many of you, it’s still warm? I had all these big ideas about how I would write an essay about winterizing a house and then turn it into this emotional tale of winterizing myself. But the emotion wasn’t there. I couldn’t find the connection. Was I waterproofing myself? Was I sealing people out? Was I keeping my warmth to myself? I couldn’t find a thread, because there wasn’t one. I don’t winterize myself. For years, I’ve been trying to do the exact opposite: to become more open, more feeling, more receptive — to be the kind of person you text when you find an owl in the road.

It was 4pm when the owl came over. I was on a walk with Cooper, taking a new trail through a kids’ labyrinth in the woods — another tree house, another zip line, another grave — talking to myself, trying to crack the bigger theme here. And I came home to find the owl deposited in my garage. I came home to a warm house, tightly sealed from the wind, but always always always open to whoever might need to come in.

Extremely invested in the future of this owl 🦉

I'm loving your Instagram footage of the owl. I really hope you can nurse her back to health and freedom. Also, I admire the ending of this post. It's better to be honest and tell it like it is, rather than bend a narrative arc or force a metaphor.