My dad wrote a book for me and my brother called Best I Can Recall. It’s a chronicle of his life “pre-mom,” and it recounts his days as a deviant and ski bum — a way to better understand who he was before he was Dad. He was adventurous, capable, “never in the CIA,” as charming or as threatening as he needed to be, and always preferred the solace of the mountains to anywhere else. Not much has changed.

My dad, Clay, spent his youth working on cars, ski racing, and evading real life. It took him 11 years to get his Bachelor’s because he spent so much time dicking around. (He would like me to add that it only took 1 year to get his Master’s.) My dad was a ski bum. He spent his winters racing, living in a house with literal cardboard on the walls for insulation. I have his racing jacket in my closet, one of my prize possessions. He gave it to me when I was 16, and I’ve carted it around for 20 years, wearing it only a handful of times out of the sheer terror of ruining something so much cooler than I am.

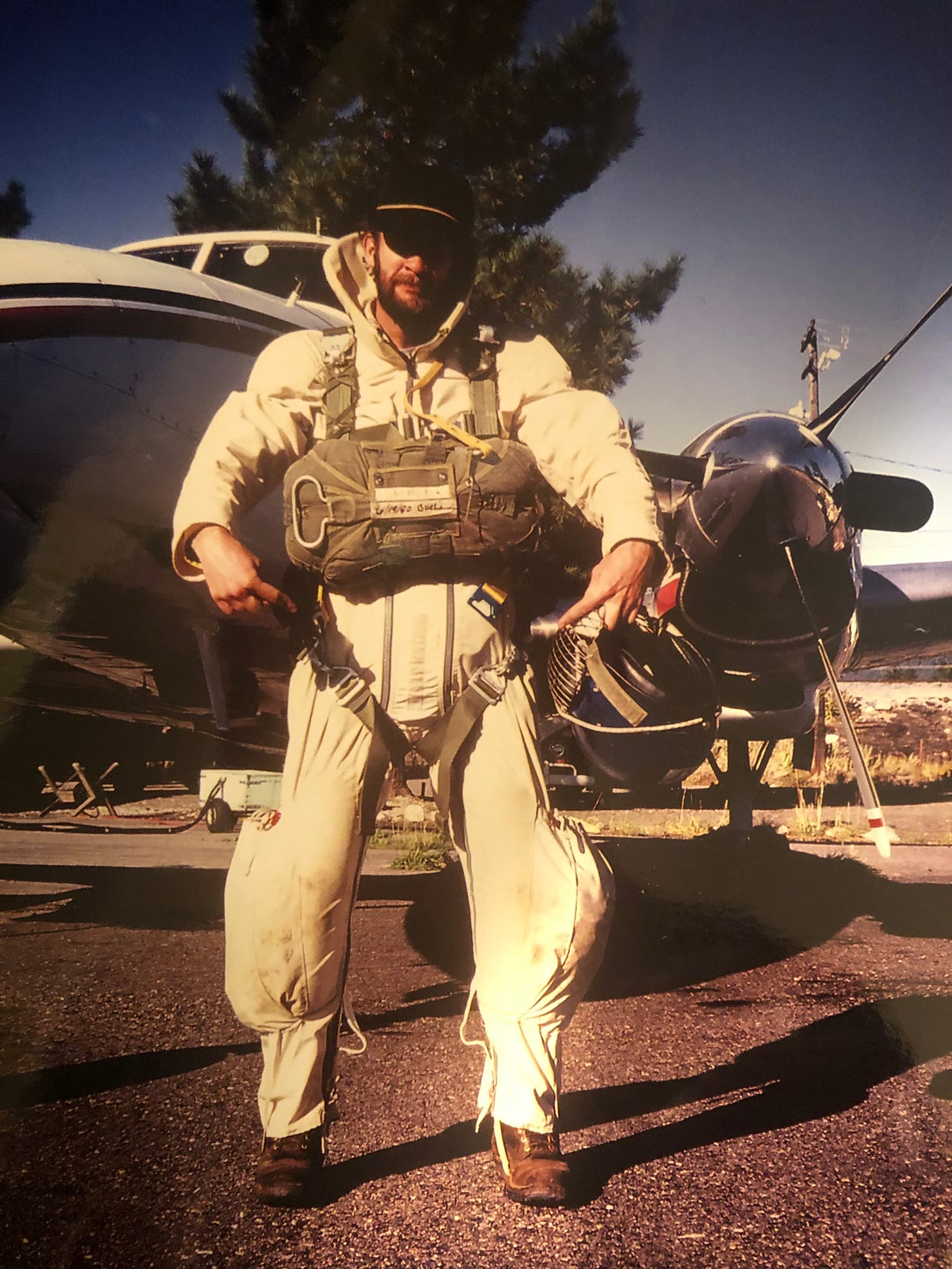

My dad’s parents moved him and his brother around a lot — some 15 times before he graduated from high school. They lived in Idaho, Hawaii, and California, but my dad’s heart was always in Idaho — it’s where he spent the majority of summers, puberty, and all his ski racing years before he eventually became a smokejumper in that same quiet Idaho town he grew up in.

One time, in a bar in New York City when I was 25, a guy struck up a conversation with me. He went the typical route, “so, what do you do?”

“I’m a writer!” I yelled. “How about you?”

“I’m a smokejumper!”

I think, based on what happened next, he had just assumed I would ask him what a smokejumper was, but instead I asked this, with such genuine enthusiasm that he knew he’d made a mistake:

“No way! Where are you based? My dad was a smokejumper!”

He wasn’t based anywhere. In an almost appealing and immediate switch to honesty, he revealed he was lying. He — and he actually said this — only said he was a smokejumper because he thought girls would think it was cool. A lot of girls might, I was ready to think it was quite cool, but I can think of one girl who never gave a shit about smokejumpers: my mom.

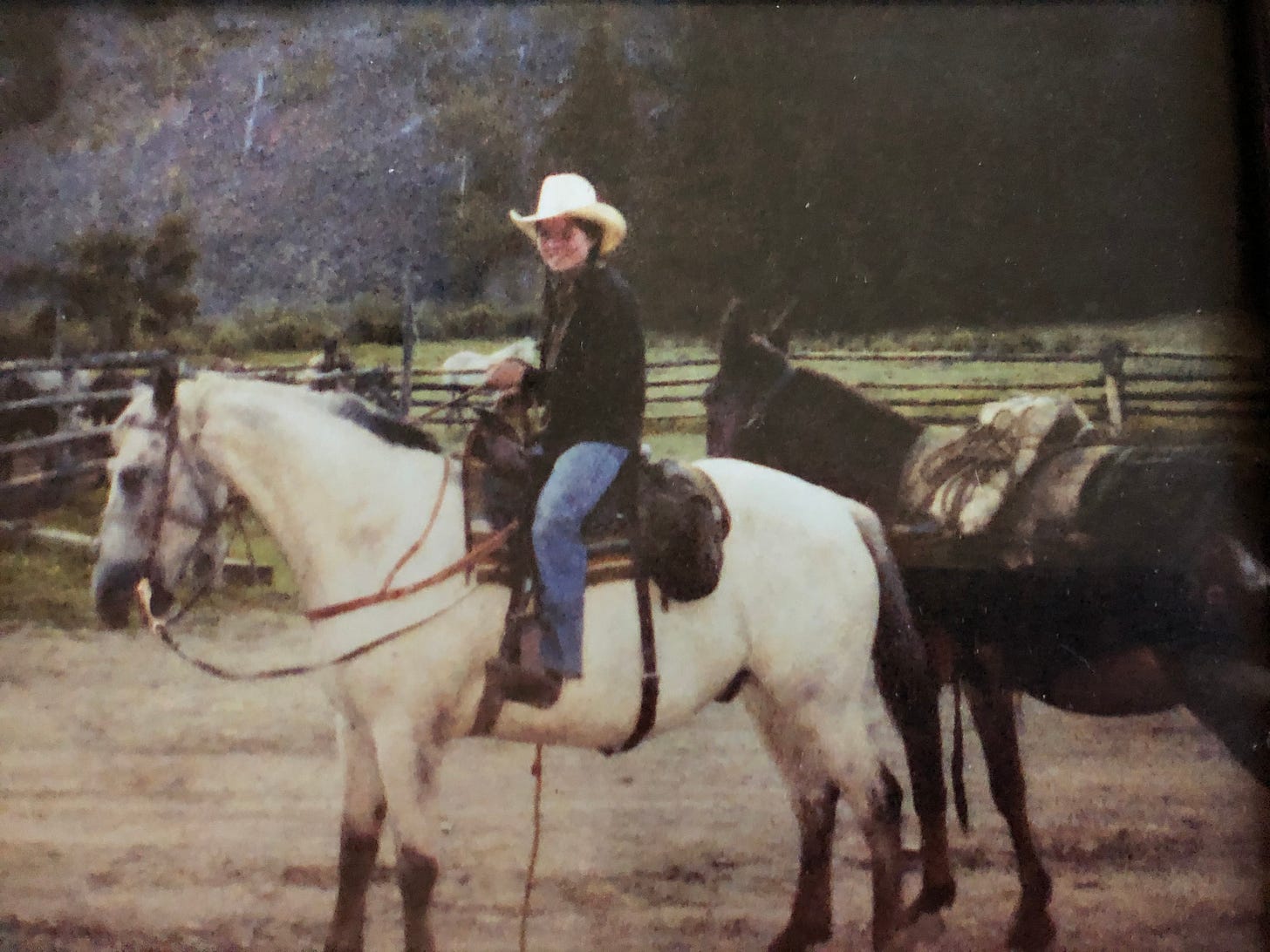

In the late 70s, my mom was as cute as she was serious. She was stationed in the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness as a ranger. She was tracking mountain lions, getting bitten by snakes, carrying dead bodies out of the woods, and ignoring men like my father.

One particularly sour day, years behind her peers on the quest for love and family (obviously, she was in the middle of the wilderness, what was she expecting?) she said a prayer. She told the heavens above she’d had enough, and she needed a sign. When was the love of her life gonna show up already? But instead of waiting for a sign, she decided to make the trip into town to get drunk.

At the local haunt, my mom was not having any problems meeting people. She was an adorable gun-toting, horseback-riding, potty mouth. A backcountry dream girl.

So when my dad walked up to her, she didn’t care he was handsome, she didn’t care he was a smokejumper, and she sure as hell didn’t care he could ski. And she made all of this abundantly clear:

“I’ve been hit on by every guy in this bar, so you better have a good line.”

I like to think my dad paused, but knowing him, we can assume he didn’t.

“You wanna get married?”

My poor father. Be careful out there — you never know when a girl has requested a sign from God and you’re about to cross her highway.

They were married three months later, and still are.

But marriage brought kids and kids brought the burden of responsibility. My dad left his sleepy little ski town, his booted feet dragging in the snow, to move East for real love and a Real Job.

And so, my parents raised me and my brother in mountain-less Ohio. Here’s a tip: The worst way to raise your kids in Ohio is to be constantly talking about Idaho. Mountains this, skiing that, tracking cougars and fighting fires, crumbling cabins and rushing rivers, their tall tales at the dinner table drowning out my lived reality soundtracked by the endless Midwest chatter of football, wrestling, and corn. This is what they mean when they say kids are listening. They’re not listening to the words, they’re listening to the longing, the hopes, the big loves. And neither one of my parents loved Ohio. They loved us, each other, and the wilderness. And so did I.

I never wanted to live in California. I had the job I wanted in Colorado in 2013. I was riding my bike to work every day, shooting whiskey in dive bars, and getting my ski legs. The big sky gave me all the room I needed to breathe. Why would I ever leave such a beautiful place?

The company I worked for had offices in Colorado, Florida, and a newer office in LA. As that LA office grew, they were looking for competent support staff to transfer over and assist with new clients. I was tapped. My boss thought I would be a good fit. I refused. Leave the snow? Are you kidding? Get a grip.

Then, a few months later, I had what one might call a very bad week. My boyfriend dumped me to move back to New York to be with his ex, my grandmother died, and my cat got eaten by a mountain lion. Dejected, heartbroken, and looking for a sign just like my mom, my boss crossed my highway with an email: “do you want to move to LA now?”

I was in a sunny apartment in southern California two months later.

As it turned out, I loved LA. I still do. But loving LA didn’t mean I wanted to be there. I worked there so I could live somewhere else. I wanted to live in a cabin in the mountains, and in 2013, the reality of what that would take and what I had in my bank account was starting to show its unlikelihood.

The town my dad grew up skiing in was his sanctuary. Some 3000 people in 10 square miles. When he wasn’t smokejumping, he was skiing. Everyone knew him — he’d been there all his life working at the laundromat, the saw mill, the jump base, the lookout, and the mountain. He was a ski bum. He just happened to get dragged to Ohio for 18 years. And as soon as I graduated from high school, he too graduated from his midwestern sentence. They moved back immediately to that small town where they’d fallen in love, picking up right where they left off with all the same friends in that sleepy mountain town. My dad was back at his home mountain, where he’d raced, where he’d taught, where he’d fought fires, back to his only responsibility being keeping an eye on the snow reports and ski conditions. The only difference now was he had a daughter to text them to. A ski bum in his element.

That was more than 15 years ago now. My dad built his dream cabin on a sloping piece of land that rolls down onto a creek bed, the mountains beginning their climb right behind the house.

But a lot can happen in 15 years.

At least once a year now you can find that quiet town on some magazine’s “best undiscovered mountain towns” list. The little cabins my dad grew up in are all gone, replaced one by one with 3000 sq ft minimum mansions that sit empty the majority of the year. Unlike the California coastline, those mansions own the slices of lakefront they sit on, eating up access and memories as they go. Traffic is choking out the wildlife, the lake is restless with motorboats, and all my favorite places to get pancakes have closed.

This has been the burden of every American mountain town since colonists came west. Every generation laments the collapse of what was once their version of perfect, usually with little regard for the fact that all this land was stolen in the first place. We were watching Greg Stump’s iconic ski film Blizzard of Ahhs the other night, and decked out in bright neon, one of the featured skiers talks to the camera about how lawyers are ruining skiing (everyone’s favorite 1980s villain.) But it doesn’t matter if it’s tech money, oil money, lawyers, AirBnb, remote workers — someone is always ruining ski towns. And it is the ski bum’s burden to save it.

Ski bums aren’t bums, and they aren’t exclusive to skiing. Backpackers, mess life, surfer bruhs and baes, all we’re talking about is people who have found their passion and choose it over capitalism’s definition of success. I married one of these people. And despite how sad movies would have written the story, “settling down” didn’t make him “grow up.” Instead, marrying him changed me. I went from the deeply capitalist view of “if I have enough money, I can live there” to the truth: “money shouldn’t have anything to do with enjoying the mountains.”

These so-called “bums” are the ones who keep the lifts running, who make these towns into functional economies, who create the “vibe” so many others are looking to enjoy a piece of. Recently, Outside+ released a podcast titled “Who Killed the Ski Bum?” It features Heather Hansman, author of Powder Days: Ski Bums, Ski Towns, and the Future of Chasing Snow. Hansman knows it isn’t just the ski bum that’s in trouble, it’s skiing in general. The sheer cost of a single day of skiing excludes countless people from experiencing the wheezing joy of slicing down a mountain as the snow sprays in your face. It holds high the image of a white person being the only one who has access to mountains. Never mind that climate change is stealing snow days one by one.

While I was listening to Who Killed the Ski Bum, my dad texted me.

It is a gift and a burden that our lives are so brief. As my father stares down the barrel of life, he is thinking about ski equipment. He is thinking about the best days of his life, the things that went into them, and how they can continue to see the sparkling light dancing through a surprise flurry of divinely crafted flakes. He is thinking about all the things he gave up, his mountain and his self, so his daughter could find her way. I imagine, as a person without children, that parents wish for their child’s happiness regardless of how it manifests, but that being able to share in that happiness makes it that much sweeter.

My father was an athlete, a preservationist, an environmentalist, a cowboy, a bad boy and a great dad. I think of him when the fires roll in, I think of him when I check my exits, but I think of him most when I am on the mountain, my shins pressed forward in my boots, my skis carving messages only the snow can read. My dad isn’t and never was a bum, but he is a ski bum. And in this new chapter in my life, that’s what I aspire to be, what I will work to share, and what I plan to protect for all the brief and snowy-eyed lives after me.

Love you, Dad. Thanks for teaching me the value of mud over money, and snow over everything else.

Hi! If I’m not mistaken I believe you are talking about McCall. My husband and I grew up in McCall in the 70-90s, both my parents worked for the payers forest service and my mom was the “secretary” for the smokejumpers for a time in the late 70s. As an elementary student I recall watching them during recess do their drills and stuff at their buildings snd grounds across from our school, and after school while I waited for mom to get off work. Ogling the smokejumpers was a thing I was vaguely aware the high school girls (in a small town the elementary was in the same building as the high school) did on their lunch breaks. ;)

My family was in that town during the final best years, before the mansions totally took over the lake front property in our tiny town. Our after school activity was to ride the school bus to the Little Ski Hill (that was the actual name) where a locker held our ski pass and gear, no lock required, and we’d ski til dark, charging hot chocolate and a hamburger on the family account and making endless runs down the hill until our folks would retrieve us at dark- or after if we got lucky!

I met my husband at 9 years old there (40+ years ago) and we are blessed to have had it as the very best place to have a childhood.

It’s different there now, just as you describe, but your blog today brought it all back for me and I’m basking in the warm memories. Even if they closed our favorite pancake house.

Thank you for this entry today.

Very moving. Thanks much (from your favorite ski bum) 😘