Today we’re talking about shit. And a little about the rules that go into creating an alpine paradise.

After Ben and I drove thousands of miles around the west, slinking around tiny towns to find our compatriots, we knew that no matter how good a town felt, we’d need to talk to someone who actually lived there to get a read.

After connecting dot to dot to dot of people, we found a guy willing to chat. Sort of.

When I called Jim*, there were children screaming in the background, somehow a delightful pairing with his Colorad-bro accent. Do you know it? To emulate it, picture a cold surfer or someone who you’re like “yes, that person smokes weed”, drop into your lower register, make “duck face” but then open your mouth, smile a little, and keep your lips in that position, and then try to talk from the back of your throat. Say things like “pow” or “dude” or “gnar.”

That’s what Jim sounded like.

I did a lot of context setting with Jim to get the right information. I didn’t care about the snow or how far it is from groceries — I wanted to know the weird shit about living in town, the stuff that only a local would know. And he shared three things:

You need to be a little bit crazy to fit in.

The Jeepers from Texas and Arizona in the summer will drive you fucking nuts.

It smells like shit in the summer.

I am a little bit crazy, and oooo boy do I love yelling at people for speeding in small towns, but the lingering scent of a town’s worth of poop? This confused me. We’d been there multiple times, though usually in the fall or winter, and had never noticed an air of ew. I asked him to elaborate. (Please, dip back into your mind’s mountain-bro accent for this reading.)

“Well ya know the houses are all like, piled in. And we’ve got like, you know, holes for the shitters. So when it’s hot it’s a real steaming shit pile out here, like keep the windows shut, man. I ain’t trying to have my neighbor’s dumps in my house, dude.”

Me either, sir. Truly. But I’d lived in a neighborhood of septic tanks for the last six years, and yes, we would occasionally walk down the steps over the precarious piece of plywood placed over the open shit hole and say, “damn, it fucking smells out here,” but that was the extent of it.

How bad could it be?

Let’s talk about town layout for a second. When I take a picture of this cabin, I have the same approach as when I take a picture of a friend: I want to get the angle right, show her best side. And that means the other houses around her (as well as propane tanks and plastic shovels and street-parked trailers) are typically cropped out. But this is an old mining town. The plots are, indeed, on top of each other.

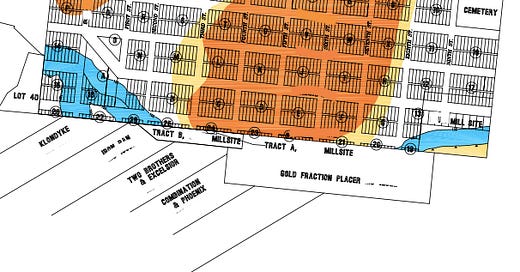

Each of those tiny little blocks is a lot. They’re small! Most people purchase two to make a 5000 square foot lot, the minimum lot size needed to build. All that orange? That’s the avalanche path. All that blue? That’s the floodplain. Which means the only buildable or built-on sections in town are the white lots. It’s limiting!

And we have a somewhat novel position in town. Most of the lots in town that haven’t been built on are actually owned by the town, and the town council would need to reach a consensus to sell them. Our cabin is surrounded by town lots. One north of us, two west of us, and several south of us. To the east is the road, and there’s a house across it. It’s about, I don’t know, 30 feet from our house? I could throw a baseball from my deck to theirs, maybe a basketball.

Town is not in a hurry to sell these lots. There is a 4% tax that goes to the town each time a house is sold here, and in 2021, the town made at least $180,000 in these sale taxes. That money goes toward town maintenance, as well as paying the mayor and the town manager. But town doesn’t own all the lots. In fact, our favorite ex-spy neighbors owned an additional lot in town, listed it last week for $370,000, and it sold in a day. In a fucking day! A lot! In a town that you have to be nuts to live in and smells like shit in the summer!

But right, back to the shit.

Some important context first: around 1960, after the full collapse of mining and milling, this town had only 1 resident. By 1990, it had 25 residents. The absolutely insane people who moved here with access to nothing had the opportunity to essentially build their dream town — and they did. In the past three decades, the town built a maintenance garage, garbage facility, two parks, a renovated Town Hall with a community garden, composting facility, new water plant and town-wide Internet. There are just 76 houses here. Even Topanga, the bucolic mountain town outside of LA that’s nearly impossible to build in because of the Coastal Commission has over 3100 houses.

But the town does not have a centralized wastewater treatment facility, so everyone has their own septic system. With tiny lots, housing sizes are restricted because of State Regulations for septic systems. Plus, county and state regulations limit the number of potential build-outs to just 150 single-family homes, lest the valley become overwhelmed not just by the smell of shit, but by shit itself.

The houses here have limitations too: if you have the typical lot (5000sqft), your house cannot be bigger than 2100sqft. If you buy four lots for a total of 10000sqft, your house can only be 2750sqft. And someone has to live in it — no short term rentals allowed. There are limits on building materials, how many bathrooms you can have, roof styles, where (and what) you can park, noise, and moto toys (i.e., no snowmobiles, UTVs, ATVs, or any Vs really.)

This is what happens when you build a town from scratch in a place that’s difficult to live — you and the other wackos get to draw out your dream limitations. And these are the kind of limitations that up until now, have kept wealth out. Think of a wealthy person, now google their house and see how many square feet it is. I will bet you real money it’s more than 2700 sq ft. (Excluding New Yorkers, though even then…)

In the early 1990s, the town also acquired and protected 169 acres of mining claims in the canyon — where our water comes from. And throughout the following decade, the town partnered with the county, the US Forest Service, and private landowners to protect more than 1100 acres in the valley from private development and commercial use, eventually brokering that acreage to the US Forest Service in 2010.

It’s a protected haven, but with the existing houses on top of each other, the septic systems are, you know, heaving. One of my favorite excerpts from the town mandate does a nice job illustrating the problem with fixing problems: “residents aren’t satisfied with dust-suppression… residents don’t want to see in-town roads paved, despite dissatisfaction with dust- suppression.” Yes, why don’t you just… come up with a magical solution that preserves my habits and interests, but requires me to change not at all. How delightfully human.

Because our lot sits pleasantly by itself, we have mostly escaped the P-U, until this past week when the strongest whiff of locker room eggs wafted into the whole house. (This is when having a deviated septum and terrible breathing habits actually comes in handy, as I thought someone was simply making eggs, not being suffocated by an army of them.)

This is the kind of thing that I would have reacted to by saying, “huh. Unpleasant. Hope that goes away.” But that’s not what happened, because I wasn’t the only one home. Someone who’d been on the planet three more decades than I had was also here: Ben’s mom. And Ben’s mom mom’ed the metaphorical shit out of this situation.

First, she inspected. Do you know what to do when the house smells like shit? Apparently the first is to check if there’s water in the toilets. In this section, I will demonstrate how completely I am not a plumber. Apparently if there’s no water in the toilet, that means there’s an open airway from the septic to your bathroom, thus letting the smells waft into said bathroom and eventually everywhere else. Put some water in, flush, get things back in order, fine. (More on that here.) But all our toilets had water in them. All showers and sinks had been in recent use.

So second, she began the phone calls. First was to our new favorite uncle and mountain MENSA member, our neighbor Aaron*.

Aaron loves to be helpful. He’s also a builder, not dissimilar from most people we meet here, and told her there was only one septic company that operates in the region, and we should call them to see when our septic system was pumped last.

The name of that septic system company? LE PEW.

Some things in life are just perfect.

So third, Mother-in-Lawful Good called Pepe Le Pew to confirm our beloved previous homeowner had actually pumped the septic like it said on the document where we signed away our lives to buy this house. But even a regional septic system company has outsourced their answering service to another country, so the woman on the other end of the line had no idea. We left a message with her to figure things out.

But the smell dissipated. Out of nose, out of mind. And like any good parent, yours mine or otherwise, the conversation turned to other dangers I hadn’t previously considered, like radon. A riveting one-sided discussion where the only thing I said the whole time was, “I don’t know.”

We’ll deal with our septic issues when Le Pew calls back, and we’ll deal with radon when another few thousand dollars grows out of the ground, but in the meantime, it’s forgotten. Jim has since sold his septic-perfumed existence for a whopping $1.2million, further confirming we got here just in time, and I continue to eye the toilets with a renewed suspicion.

We’ve reached a time when paradise (often a place that’s deemed as such because it escapes the unending onslaught of making convenience more convenient) needs protecting from convenience itself. You can’t make a house as big as you want. You can’t just add a bathroom because you want to. You can’t clean your car whenever you want. You can’t climb the mountain however you want. You can’t build there, you can’t do that, you can’t you can’t you can’t because the more you do, the more you destroy. But the more you limit, the more you limit people. Inevitably, in a place with only 76 houses, the rules of supply and demand kick in. And as evidenced by the recent sales, they’ve kicked in hard.

When we were scouting this town to be home, I made a spreadsheet that tracked every house, when it was sold, what its cost per square foot was when it sold versus what it is now, and included beds, baths, and other details. All my data showed me one thing: we needed to buy in 2021 or we would be priced out in 2022. And that proved to be true. Ben and I both have town jobs now, mine in addition to my remote job, and we’re honestly beside ourselves that we get to be part of this community where the wind blows out your windows, the snowdrifts bury your doors, the neighbors know your business, and the prettiest days smell like a frat house bathroom.

We couldn’t ask for more.

Being older and having grown up with septic lines, my dad would occasionally set it on fire. Like magic it stopped smelling for awhile

I dated a guy for 8 years who worked with his dad in their septic pumping business called "Septic Alert." I know waaaaay more than I ever wanted about the finer details of septic tanks and what it's like when things go wrong.