By the time this is in your inbox, I’ll be in the Bob Marshall Wilderness on a pack trip with my mom. We’re riding along the Chinese Wall, a continuous cliff band along the Continental Divide. Because we’re going with an outfitter, this will be a comfortable trip. Our dry bags and canvas satchels will be mule-packed, and we’ll be treated to fire-cooked meals every night. In my own dry bag I’ll have the usual base layers, riding jeans, work shirts, and boots, but the pack train allows me to bring things like a book, the notebook for my morning pages, and other creature comforts for the tent.

I’m excited to spend time internet-free time with horses, but this isn’t a trip I would have selected myself. I’m going because this ride is on my mom’s bucket list, and I know my dad would be more than happy to never get on a horse again. My mother is a horse woman. She raised me on Misty of Chincoteague and Wild Hearts Can’t Be Broken, Breyer horses and hay bales. I was 7 when I got my first horse, a $500 mare from a woman who couldn’t ride anymore. The only girl to ever get a horse without asking for one. It wasn’t really for me, after all. My grandfather had been part of the Cleveland Mounted Police, making my mom a city kid with unusual access to the stables, to the smell of manure and the power of horses — making her a horse girl.

Making fun of horse girls has been a national pastime at least since I knew what pastimes were. Nerdy and braces-bedecked, fawning over and fantasizing of a power they didn’t have. That is really what women have often had in common with horses for centuries: powerful creatures bridled and immured, held in paddocks for domestic labor. Kept but born for something else. Our bond is in our capture. Our love is in our escape. Wild horses need breaking, and that’s not a far cry from what society wanted for wild women. We’d never say a man is hard to handle, but we’d say it of a woman, and we’d say it of a horse. People said it of me.

Growing up, despite the inherent danger of riding a horse in my backyard, my parents never let me wander further than the driveway as a kid, always warning me about men hiding in the backseat, men waiting under the car, men talking to me in any capacity at all. They desperately wanted me on the straight and narrow, in direct contrast to their own circuitous paths. Their worst nightmare was me moving to New York City when the worst things that happened to me were in North Carolina. As I got older, and they were willing to share more about their lives and their reasons, they were the same as any parents: trying to protect me. I think they’d say I never listened, but I’d say it took me much longer to listen to myself than I’d like.

In any regard, New York was never dangerous, and it didn’t hold a candle to the danger my parents put themselves in. My dad, jumping out of airplanes into forest fires. My mom, living alone in the backcountry in the 70s, something I think they would have directly forbidden me to do. Something I might’ve done anyway had I not been so terrified of being poor.

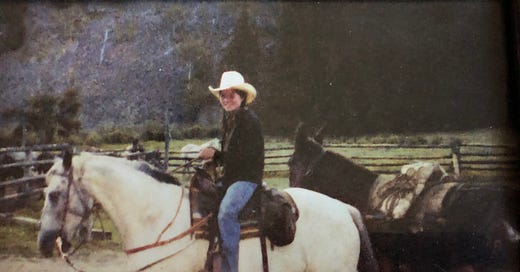

Before my mom’s tenure as a wildlife biologist at a clinic in Ohio, she was a ranger in Western Idaho, a far cry from the streets of Cleveland. It was rare then to see a woman in the backcountry. The man who hired her told her to her face he was disappointed she wasn’t Black — saying he would have been able to hit two diversity stones with one placement. Not exactly an inclusive, welcoming workplace. But my mom isn’t a daisy. She is an oak: stubborn, strong, unafraid of shedding limb and leaf when it suits her. She had (and has) no qualms speaking her mind. Plus, she had friends of her own in those woods: the horses. Part of her work as a ranger was running pack trains. She tended to the horses and mules, and in turn, they cared for and carried her. This week, in honor of a little mother/daughter bonding, in honor of our deep love for horses, here’s an essay of hers, one I love to bring up when parents worry about me.

Head to Tail by Maggie Wright

As any morning in the backcountry, the air was chilled and the crew was wrapped around the wood stove, clutching our coffees and awaiting our assignments. Some people would be sent off to build fence, others on standby for fires, and my boss Lee and I were still figuring out our patrol routes for the day. The stillness didn’t last long — a frantic, disheveled man on a worn-out horse appeared from the dirt road screaming hysterically.

“Oh my god, he’s dead, he’s dead, please help us!”

In a vast wilderness, eighty six miles to town on a dirt road, help was hard to come by. Frequently the only emergency help was the nearest Forest Service station — and in this case, that was us. We had dealt with many mishaps before, so Lee and I tried to calm him down to get a coherent account of what had happened but he could just cry and sputter near nonsense.

All we knew for sure was that someone was badly injured, so Lee and I ran to the barn across the dirt airstrip to prepare for a trip into the backcountry. Rusty and Scrap were good sound horses but trying to figure out which mules to bring was always interesting because unlike horses they decide at any given moment whether they are either going to participate or not in any given situation. We packed the two mules we thought we could count on the most with large canvas manties to carry our assorted tools, not knowing exactly what we were in for but knowing it was a bad situation. Our imaginations were in overdrive, but we weren’t even close to the reality of what was ahead.

Ten miles down the trail with a packstring isn’t made in a hurry but as we headed deeper into the wilderness with the lone hunter, parts of the story began to unfold. They were just having a good time. These guys thought of themselves as seasoned elk hunters. They hunted together every year. Perhaps there was a little alcohol involved — there usually was. His friend had just been walking down the trail. How could something like this happen? How could it all go so wrong?

As we came upon the rest of the group, it was obvious they had stayed to guard the remains of their friend from likely predators. All of their faces were blank. Shock had set in. As Lee and I unmounted, the story was obvious. The man had been walking down the trail with his muzzle pointed up towards his head. He had tripped, and the muzzle went off, blowing apart his skull.

Those first few seconds were spent visualizing the story as it must have happened. The next minutes were spent dry heaving as bits and pieces of what had once been a living person were spewn upon the rocks, the trail, and the rest of his body. I don’t watch horror movies but we found ourselves in the middle of one. We couldn’t call the sheriff until we were back in radio range, the hunting group was incapacitated beyond any scope of the imagination, and I couldn’t stop throwing up. I knew we had a job to do but at that moment I wasn’t prepared in any way. I put a bandana around my face trying to hide from the flies, the smell… from everything.

Lee and I had to buck up. We took the manties off of the mules and laid them out on the ground. There was a body to bring back to the ranger station, there was a report to be made, there was a duty to follow. We picked up the body, wrapped him in the manty and like any other load we had ever put on our mules we tied the knots, we hefted what was left onto one of the mules and secured him to the pack. The mules were used to raw meat being strapped to their backs. But for me, this was different. The bandana was useless. I was still puking and I couldn’t stop crying.

Lee and I cleaned up the area as best we could, burying the smaller pieces. Predators would arrive soon either way. The smell was undeniable. We helped the rest of the hunters gather their camp and had them follow us back to the ranger station. The quiet of the forest settled around us, the only sound was the scraping of hooves against the soft ground.

We followed protocol. We radioed the sheriff in Yellow Pine who would come over to finalize the investigation. We radioed Forest Service dispatch in McCall to send in a plane. We offered his friends what little solace we could. This was not my only retrieval of a person who had passed in the backcountry but those were from natural causes. This was trauma at an unbelievable level — and it was just part of the job.

Shangrilogs will be on hiatus this Wednesday and next Sunday while I’m in the backcountry, returning to the paid edition on July 19 and the free Sunday newsletter on July 23.

Here’s hoping our time in the woods is a little less eventful than my mom’s.

I would buy a memoir by your mom in a heartbeat.

What a wonderful time for you two! Enjoy your time together. That story...wow. She is made of tough stuff and I can see where you get your grit